HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO ALE, BEER AND THE LICENSING LAWS

By John Hodges

There is no actual date that can be accurately attributed to the first appearance of alcoholic beverage. It most likely occurred as a result of the natural fermentation of fruit, the ingestion of which by early man was noted for its soporific effects. The first mention of what we would describe as ale occurred several thousand years ago and is referred to in the ancient Egyptian work entitled “The Book of the Dead”. This work refers to the preparation of an intoxicating beverage prepared from grain, whilst the celebrated Dr. Birch Egyptologist claims through hieroglyphic translation that this beverage known as “heqa” existed as early as the fourth dynasty and was in fact made from red barley or malt. Other ale from this period came from Kati a country to the east of Egypt , where at least some of the production was used for medicinal purposes. There is little doubt that the ancient Egyptians indulged in ale and understood its effects, as papyri of the time of Seti 1 around 1300 BC, attest to the intoxification of a person who had partaken in excess. Diodorus Siculus states that “wherever the vine was not found in Egypt Osiris taught the method of preparing a corn wine from grain”. This statement lends credence to the view that ale from the earliest time was the natural substitute for wine in the countries where the grape did not flourish. The brewing of ale was by no means the exclusive gift of the Egyptians, the Hebrews themselves had their own word for such a beverage “sicera”, which is translated in the Bible as strong drink. Within the text of the Bible differentiation actually occurs between the various intoxicants, where the words “wine and strong drink” are used to clearly indicate that wine alone was not the only imbibement available at this time.

As proof of the continuing spread of ale Pliny wrote of “The several nations who inhabit the west of Europe have a liquor with which they intoxicate themselves, which is made of corn and water” This beverage depending upon where it was brewed was known by a variety of names, Zythum, Ceria, Curium, Cerevisa they were all descriptive of mankind’s new found ability to make water itself intoxicating. Whilst all of this was happening in Western Europe the ancient Britons continued to produce a fermented liquor made from barley, honey or apples, but with the advent of the Celts there most certainly came the knowledge needed to brew ale. They either brought with them or acquired the knowledge and practice of agriculture a science that the production of ale demands. The coming of the Romans further improved the methods of brewing and when our next group of visitors arrived, the Saxons already an ale imbibing race, they too added their knowledge to the process. By the ninth century ale had become the general drink of the country, and it was not uncommon for rents to be paid in malt and ale. Although there was a temporary decline in the popularity of ale brought about by the introduction of French wines that accompanied the Norman Conquest, supremacy of ale was restored by the twelfth century. English ales by this time had found fame on the Continent, especially those brewed by the monasteries, in fact following the reformation many of the displaced monks found alternative occupations engaged in the brewing trade.

The use of hops for flavouring beer was well known on the continent, and as early as the time of Pliny the Germans were brewing ale with the addition of hops. Prior to the use of hops attempts were made to flavour ale with aromatic and astringent plants, even oak bark being used for the purpose. It is traditionally held that the introduction of hops into the brewing process is what led to use of the word beer to indicate the presence of this female flower of what was once regarded as a salad variety of the nettle plant (humulus nupulus). Hops are commonly supposed to have been introduced into England around the middle of the fifteenth century, but this may well be incorrect as there is some evidence to suggest that the Saxons used them in brewing. Certainly there are references in literature of this time that talk of the “ale of bitterness” one of the properties imparted to traditional ale by the introduction of hops into the brewing process. For many years the distinction between ale and beer persisted but as the addition of hops came into general usage the two words became synonomous .

DEVELOPMENT OF THE LICENSED TRADE

It is an interesting fact that in early times a great deal of brewing was carried on by women, up until the eighteenth century the brewing of beer in country houses was still recognised as the duty of the housewife. Within literature frequent references were made to ale-wives an attestation to the proliferation of the fair sex within this trade. In the reign of Henry IV the brewers of London formed themselves into a mutual society, and in 1445 they received their first charter. The formation of this Brewer’s Company offered some protection to its members from the continual round of disagreements over measures and strengths of their products, but did little to legislate for the ongoing variances that still existed between the brewers of ale and beer. It was not until the reign of Queen Mary that the brewers of ale and beer became united under a single corporate body and it was probably this action that raised their standing with the regulatory authorities and banished for ever the unjust treatment that for so long they felt had been their lot. During the reign of Edward VI the London brewers obtained a decision from the Common Council that only two kinds of ale should be brewed, single and double each being a function of the amount of grain fermented during their brewing. However many of their customers insisted upon combinations of these brews and in order to circumvent the sheer logistics of serving the same drink from different casks a man named Harwood prepared a composite brew which quickly became known as porter. Over the years the once popular porter has gradually been replaced by mild ale although with the advent of the new crop- of micro breweries it has for some made a most welcome return.

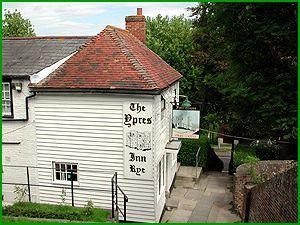

A tremendous stimulus to the brewing trade occurred during the eighteenth century whereby the wealthy classes who had previously brewed their own beer began to find that it was cheaper and less troublesome to obtain their supplies from an independent brewer. This same class were often the nobles and landowners who dispensed open hospitality to the traveller but eventually even they transferred this accommodation to an inn set up in the vicinity of their land with the innkeeper usually being a retainer of the landowner. Many of the taverns and public houses of today have evolved from the almonries that were attached to the monastic establishments when the duties of hospitality were discharged by the church. In the large towns and cities inns and ale houses existed as far back as Saxon times and records still exist showing the relationship that existed between landlord and guest. As the numbers of these public houses grew over the years, so did the expectations of an acceptable standard of décor by both their customers and the licensing justices. By the early eighteenth century licensees were experiencing great difficulty in providing enough capital to maintain their premises even at the modest standards that accompanied such expectations. It was the maintenance of these standards that initially paved the way for what was to become the tied trade or in the language of

today’s commerce, the pub became part of a vertically integrated business chain. What actually happened was that the brewer came to the aid of the licensee by providing a loan for the refurbishment of the premises to an acceptable standard, conditional upon the borrower obtaining his supply of beer from the lender. This proved satisfactory until such times as the licensee offended against the licensing laws and was called upon to forfeit his license with the consequence that the brewer not only lost the outlet for his beer, but his money as well. Brewers soon realised that they could exercise far greater control over such matters, and protect their capital more effectively, by acquiring the premises and letting them to a suitable tenant. This new system spread rapidly throughout the nineteenth century, not as a result of expansionist aims on the part of the brewers, but because of the financial needs of the licensees, and the needs of the brewers to maintain outlets for their product. Beyond the tied system, which to a great extent was dismantled by the recent changes that came out of Lord Young’s report, there has always been the free house and the managed house. The managed house is usually a large new establishment where the brewer feels that the amount of capital invested in such a venture requires the profit from both the retail and wholesale side of the business to give him an adequate return. Conversely the very small houses are invariably tenanted as the administrative costs of management would be disproportionately high in relation to turnover. Many small pubs, especially in the back streets of towns and in rural parts, would disappear under any other system than tenancy. It has been the case over many years that these small tenancies permitted the landlord to take on a second job, whilst the running of the pub was very often left to the tenant’s wife. Indeed many of the small pubs and beer houses that existed in the working quarters of Hastings and St.Leonards fell into this category, whereby a second income was necessary to sustain its very existence.

LICENSING

It is not my intention to dwell upon the vast subject matter that comprises the numerous licensing laws out of which our current system has evolved. Suffice it to say that for the serious student such matters are eruditely dealt with in several Justice’s Manuals published annually as veritable tomes. For my purposes comment is restricted to those salient dates that either proliferated the existence of the public house, or brought about its demise.

Control of the licensed trade, which has largely been organised by a system of licenses granted by justices of the peace, dates back to 1495. Henry VII first gave powers to the Justices to enable a system of control over the propagation of drinking establishments by means other than pure market forces. By 1552 Edward VI’ s “government of wise men” further extended these powers with the introduction of the first Justice’s license and the creation of the Brewster Sessions. This licensing act also sought to prohibit unlawful games, outlaw drunkenness, and set up the powers of the constables to present an annual list of licensed ale house keepers, or tipplers as they were then known, to the licensing justices. The two main objectives of licensing law were to control the amount of drinking, and to protect the public from any monopolistic exploitation that might be associated with the granting of licenses.

Justices have always held wide discretionary powers in the administration of the licensing laws, and only in the period 1830 – 1869 were their powers partially removed. An act of 1830 provided for a beer house to operate merely on the payment of an excise license, and without an accompanying Justice’s licence. This legislation provided only for a house selling beer, as those selling wines and spirits still required a Justice’s licence. Needless to say this act was the catalyst in the proliferation of such establishments many of which were in a squalid condition, virtually unpoliceable, and contributory to the rise in drunkenness. In 1869 another act was passed that sought to return the responsibility for the grant of licenses to the licensing justices. The consequences of this legislation was a vast reduction in the number of licensed premises, although it still offered limited protection to all of those licenses granted prior to 1869. Even the provisions of this act were not considered sufficient to satisfy the Royal Commission on the Liquor Licensing Laws (Peel Commission) that reported in 1899. Further large reductions in licensed premises were still a requisite for effective policing, and the improvement in status of the premises and the licensee in general. At this point the only reasons open to the licensing justices for the removal of a licence were based upon the improper management of the beer house, or the bad character of the applicant. The licensing Act of 1904 that followed the publication of the Peel Commission now provided other means by which existing licenses could be extinguished. The main feature of the Act was to set up a fund by exercising a levy on the existing licences within the district, for the purpose of providing compensation to those licensees who then lost theirs. This Act provided for the removal of licenses not only on the basis of transgression, but also on the grounds of redundancy. This allowed the authorities to prove by a series of inspections that a need no longer existed for a particular pub, usually in an area considered to be over populated with such establishments.

These new measures had the effect, particularly in the Old Town of Hastings and central St.Leonards, of greatly reducing the numbers of beer houses and pubs that had been born out of the 1830 relaxation of the licensing laws. During the latter part of the twentieth century the closure of pubs as a direct result of the provisions of the 1904 Act reduced to the point of non-existence. The continuing existence of licensed premises was now no longer a question of its need, but dependent upon its continuing financial viability for its owner. Thousands of pubs have been lost as a result of legislation enacted for a variety of purposes. Some being directed at saving lives through strict controls on drinking and driving, and the consequential reduction in patronage, whilst other legislation sought to impose expensive and sometimes financially unviable investment in all manner of “improvements”. Whilst any legislation directed at preserving life must be applauded, the invasion of the licensed trade by speculators who recognised the freehold potential of struggling country pubs is far less palatable. However all of this activity served to reduce the available choice to the discerning drinker, as too did the limitations placed on the hours through which a landlord could legitimately ply his trade. Whilst restrictions began to be placed on the opening hours of licensed premises from the middle of the nineteenth century, drastic reductions were introduced at the start of the First World War as part of the Defence of the Realm Act. Over the years minor and seasonable adjustments have been made to the licensing hours but it was not until the Licensing Act of 2003 (effective November 2005) that significant relaxation on a permanent basis was offered to the licensed trade.

THE LICENSED TRADE TODAY

Now that the Licensing Act of 2003 has truly bedded in and its effects can be qauantified, the loss of the traditional public house has been accelerated. Admittedly this statement must be modified with the conditions created by the current financial climate, and the changes in drinking habits. Although both Hastings and St.Leonards have lost a number of their traditional public houses over the last few years, it has in turn seen the growth of the licensed bar and restaurant, both endemic of this change in drinking habits. The introduction of the ban on smoking in public places, although most welcome has also contributed to the demise of the once popular street corner local, where smoking and drinking were practiced as complementary enjoyments. The wain in the practice

of the traditional pub game such as darts and shove halfpenny, has affected that part of the midweek trade that was brought in by their avid exponents and supporters. This coupled with the long held practice of annual prizes and a beano being provided by the brewers who were involved in the tied trade system, and encouraged those activities that formed such an important part of their marketing strategy. Now the basis of entertainment is focused solidly around the provision of music , with the pub quiz provided to stimulate the intellect of those who aspire beyond the questionable delights of the karaoke machine. It would be unfair to write off the licensed trade in general with such broad accusations, as many wonderful public houses both in the town and the countryside still shine through these “mists of progress”, and continue to uphold the traditions for which the English pub is famous throughout the world.

“Rye’s Own” February 2012

All articles, photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2015 Cinque Ports Magazines Rye Ltd., Guinea Hall Lodge Sellindge TN25 6EG