“A Summary History of Rye”

The Printing Reformer

by Rya

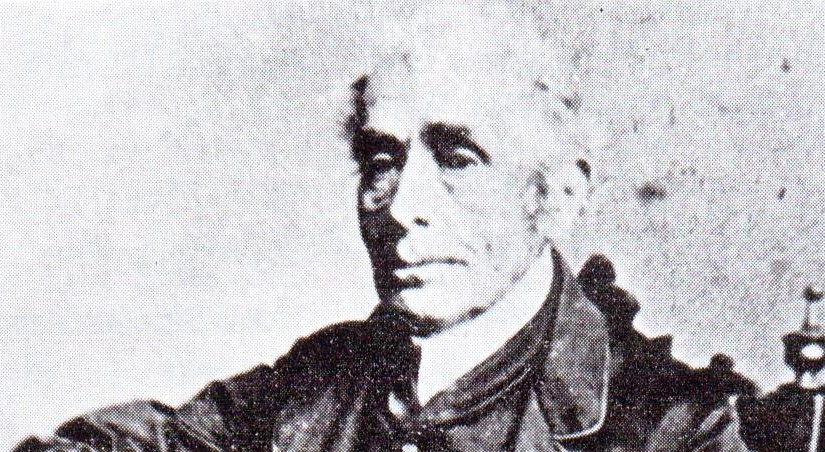

Part XVII — Henry Pocock Clark

In 1861 H. P. Clark’s printing office in the High Street issued “Clark’s Guide and History of Rye,” a small volume of great interest to the local historian for much that is recorded therein is not to be found elsewhere. Written in a witty and amusing style, often interspersed with verse, the author revealed probably far more than he intended to tell about himself. Born at Brighthelmston on 4 September, 1797, Clark received a lower middle class education intended to prepare him as a tradesman. At 14 he left school and soon found that his learning was… “deficient of substance.” When he was 21 his father established him in business on his own account, which he carried on with little success until he quitted his home town for Rye at the age of 30. About two years after his arrival in the town he decided to become a printer because the only other printer in the town had “refused to print several things that were against the old corrupt system, carried on by the patron of the borough, Dr. Lamb.” Knowing nothing about the trade, he sought the advice of a type founder in London as to what he would require. His account of the interview is rather amusing.

“You will want, said he, so much of Brevier, so much of Long Primer, so much of Pica, and so much of Fat-Face Pica. Here I was quite at a stand; Pica, I wondered what Pica meant. He still proceeded, so much of Great Primer, so much of Double Pica. What ! more Pica, thinks I. How I wondered what this Pica was; but I dared not show ignorance, as having previously given him to understand that I had been in the trade. Well, he proceeded, you will want so much Canon, I nodded assent and was as wise as ever, so much of 4-line Pica, 6-line Pica, 8-line Pica, and 10-line Pica. This was a stunner and no mistake. There were two thing that I was sure of, that I knew nothing what Pica was, and that I never should forget the name. Now, says he, you will want some furniture; but whatever furniture meant I knew not, it was equally as foreign as the rest. but there was no more Pica.

In the course of a week I was garretted in Rye;

that was, I had my Press, Pica, and Furniture, safe in the garret, and no one knew any thing of my intentions.

At a political meeting held by the reformers at the Red Lion soon thereafter, Clark officially announced his new profession with the consequence that most of their posters, manifestos and squibs were printed by him. Although at first his work was by no means of the highest quality, he became highly proficient and produced some very fine typographical specimens.

A consideration of some of the subjects discussed in the “Guide and History” will reveal his outspokenness as well as much that is of value to the local historian. Of the Court Hall in Market Street he writes:

“Here law is plentiful, and that of the highest price. Dear things are cheapest in the end, At least so many say, If you are summon’d to this court Then you will dearly pay. Get drunk in town, kick up a row, Five shillings, and no more; But, if you do the same in Rye, You’ll have to pay a score.”

Naturally, his opinion of lawyers was not very high:

“If lawyers should to heaven e’er go, Then, this I know full well, There’s not a man, woman or child Will ever go to hell.”

Amazingly, however, the town possessed three honest lawyers, a fact Clark thought should be recorded in verse:

“Exceptions to a general rule I find them now and then; Here’s one, three Lawyers lived and died All good and honest men.”

If the lawyers were scoundrels, the clergy were little better. Many of the Methodist preachers

“are not of the first class, for it is an old saying, ‘Anything will do for Rye’. In fact, many of them show as great a desire for the ‘Loaves and Fishes’, and are as great tyrants, as any church minister”

Of the “high Calvin” chapel at the foot of Rye Hill built by Mrs. Jeremiah Smith, “who is very desirous of doing good to her fellow creatures, in a religious point of view,”

Clark writes:

“There many folks on Sundays meet, with motives widely odd; Some go to worship Mrs. Smith, And some to worship God.”

One of his most sweeping criticisms is reserved for the intellectual qualities of the Ryers.

“Rye, with about 5,000 inhabitants, for sterling intellect, or great men, is as bare as trees are of foliage in winter. It has but one (Mr. Holloway), who is the only star of any magnitude shining in its hemisphere, whom Rye is proud of; a man who has been, and still is, one of the most consistent men of Rye; and his honest and straightforward intentions have caused many base men to strive in vain. His harangues are in a mild tone, with a certain degree of candour, conscientiousness, and patriotism;

“It is somewhat curious to relate that almost every merchant, tradesman, farmer, and the pa and ma gentry, sprang from humble parentage. And yet, any one now in the same humble circumstances would, by the above, be considered too mean to be noticed, being of low origin. Pride, pride it is a silly thing, Yet, here ‘tis carried high; Few are the towns, in this respect, I think, can vie with Rye. The humbler and higher classes, generally, would not do for trainers of morality; and as for their wisdom it is not very attractive.”

Although all the shops were closed on Sundays, the inhabitants were far from religious.

“Do as you would have others do, Ah! that is all my eye. Now, that may do for other towns, ‘Twill never do for Rye.

For many of the inhabitants deem it Far worse to whistle on a Sunday Than cheat their neighbours on a Monday. Of hypocrites plenty we have, Of God-fearing people not so; And God-loving people, I think, Not far in the units will go.”

As regards the modernization of the names of the old streets and the historic buildings therein, Clark was outspokenly opposed.

“Antiquity”, he writes, “is all that Rye can boast of. Then why rob it of that?

“Now, there are some upon this globe, We call them Yankee Doodles;But, you wont find beneath the sun A place like Rye for Noodles.

Whenever the rulers of the town are aroused from their somnolence, they will not know the names of the streets they live in. There is a saying, true it is, Which no one can deny; It matters not what it may be, That’s near enough for Rye.”

What is the verdict of posterity on this blunt, honest, independent and critical man (whose outspokenness may not have endeared him to his fellow Ryers) and his “Guide and History”? L. A. Vidler, the modern historian of Rye, dismissed him briefly in evident distaste but, although his book is fragmentary and sometimes unreliable, it is often illumination. If his work lacks the scholarship and precision that so nobly distinguished Holloway’s “Antiquarian Rambles”, a student of the period would only ignore it at his peril.

From the 1967 Issue of “Rye’s Own”

All articles, photographs, films and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2016