The port was always used for commerce as well as military purposes. The Romans shipped much of their iron exports from it, for even in Roman days the Weald of Kent and Sussex were producing iron.

Iron shipped from Rye during the Middle Ages is known to have derived from Beauport Park, Sedlescombe, Brede and Crowhurst. In the years 1632 and 1633 Rye sent 394 tons of iron to London, 99 tons to King’s Lynn and 30 tons to Sandwich.

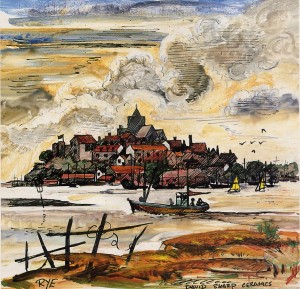

But with the inexorable eastward march of the shingle, Rye found itself farther and farther from the sea and it became harder and harder to keep the mouth of the Rother open. By the sixteenth century Rye was classified as a fifth-rate port. A survey made in 1562 of the Rother’s course from Newenden to Rye showed that the channel had become narrow and shallow. In 1618; ‘now is our harbour decayed and all trade forsaken us!’ To-day people who know a little about Rye (including people who live there) will tell you Rye is finished as a port! In fact Rye is developing as a port, and may develop further yet.

There was a recession in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but in the nineteenth century Rye was a flourishing port. At the beginning of that century there were several fast forty-ton sloops sailing a regular packet service to London besides a small fleet of larger vessels. We know, for example, that the brig William, 108 tons, built Rye 1815, master Captain Samuel Vidler, crossed to New York with a load of emigrants in seventy-one days. This brig was eventually lost off Holy Island, Northumberland, in December, 1851.

In 1865 there were fifty-six merchant ships registered at Rye, although several of them were owned by people who lived in Hastings. Rye had become a considerable ship-building place. Hoad Brothers, Hessel and Holmes, Mills and Sons, G. and T. Smith, were all building ships or barges, and a traveller to Rye in 1855 saw seven ships a-building all between 200 and 300 tons. The Smiths built many sailing barges.

In case there are readers who are not familiar with the East Coast, who might take this word ‘barge’ to mean a river barge, or confuse it with the ‘narrow boat’ or ‘monkey boat’ of the narrow canal system (the one with the roses and castle painted on it, which is not a barge at all but a boat), I may here explain that the East Coast sailing barge was one of the finest sea-going ships ever evolved. Carrying from a hundred and thirty to over four hundred tons of cargo they traded all over the North Sea and English Channel and some of them even crossed the Atlantic under sail. They were only called barges because they were flat-bottomed so they could get into shallow harbours such as Rye. Smiths built the grand old boomie barge Martinet that eventually floundered in Hollesley Bay in 1941 after having been shaken up by a German bomb. Captain ‘Bob’ Roberts wrote a fine description of her last hours in his book, The Last of the Sailormen. He was her mate at the time. Rye was the most considerable barge port on the south coast. The spritty, Olive May was the last barge to be owned there.

Hessel and Holmes built the Madeira Pet, a wine and fruit schooner of 83 tons, 97 feet long, 18 feet beam. She was launched by Don Miguel, Pretender to the throne of Portugal. In 1857, while in Guernsey owner-ship, she became the first ship ever to sail from Europe to Chicago! She sailed there from Liverpool, with 240 tons of cutlery, earthenware, paints, glassware and chinaware, and she loaded 4,000 cured cattle hides back, together with a barrel of cured whitefish as a present for Queen Victoria! Her arrival in Chicago, so far from the sea, caused great celebrations in that city.

In the middle of the nineteenth century plenty of these fruiterers and wine carriers were owned in Rye. They were vary fast schooners, driven hard by small crews of tough men. Many a time a fruiterer has left London, reached the Downs at a time of south-west wind, sailed straight through the fleet of merchant shipping anchored there waiting for the wind to change, loaded in the Mediterranean, and sailed home to find the same ships still waiting in the Downs! These handy little schooners with their for-and-aft rig, fine lines, and liveliness on the helm, could be driven against the wind like modern ocean-racing yachts. If steam had not come to knock them out who knows how sailing ships might have developed?

By the turn of the century, although far fewer ships were owned in Rye, the harbour was still working about two hundred cargoes a year. These were mostly coal in, corn out, Dutch cheese in, Susses oak trees out. Much of this trade, though, was carried in West Country schooners. But in the First World War trade declined to nothing, and after the war it took a long time for trade to build up again. The first cargo in a load of roadstone from Ostend in the sailing barge Alde came soon after 1918. By 1933 there were from seventy to eighty cargoes in a year, mostly in barges. Rye owned then about ten big ketch or ‘boomie’ barges and several ‘spritties’; the former carried about two hundred tons, the latter around a hundred and thirty.

Trade & The Cinque Ports Commitment

One of the very earliest references to Rye was in 1105, when a mention of a “Fine large ship from Rye” appears in a contemporary document of the time.

It became an ‘Ancient Town’ and, along with Winchelsea, was invited to join Hastings, Romney, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich to form the Cinque Ports Confederation.

The Confederation was concerned only with building fighting ships and providing the men to sail and fight them, but all the ports were building merchant ships to import goods and barges to move goods up the rivers and canals to inland destinations.

Rye seems more than probable that before the first recorded history of the town of Rye ships were being built here and moving large cargos in and out of the port and to inland destinations, a trade that has carried on to this very day.

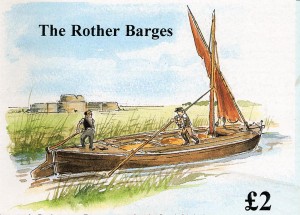

The Rye Barges

The earliest reference to Rye barges appears in the Rye records of 1531, the design and sail rig of these barges had hardly changed in 400 years.

Primrose, recently rescued from the mud on the banks of the Rother and taken to the Hastings Fishermen’s Museum for renovation, was built in 1890 in Rye. She was part of a fleet of barges which traded on the River Rother, the Royal Military Canal and associated inland waterways. The bow section of another member of the fleet – Waterlilly – still lies on the bank in Rye Harbour but her construction is not as important as that of Primrose.

These barges, powered only by sail, were crewed by two men often a father and son team. They could carry about 30 tons of cargo which included coal, chalk, sand & salt carried upstream from Rye; the return cargoes included timber, bricks, stone and hop poles.

In the 1890’s there was a significant coal trade. The coal was loaded loose in Rye and sacked on board during the voyage. At that period some 13 barges were involved in this trade. The cargo was loaded into the barge using wooden wheel barrows which were wheeled across a narrow plank joining the barge to the river bank.

Primrose worked on this trade until 1937 when road and rail transportation became more competitive. Until 1940 she was used for harbour works in Rye but was then laid up on the banks of the river.

The Fishing Fleet

Fishing has been a major contributor to Rye commerce. Fish from the local boats was transported to London by ‘rippiers’ using pack ponies as far back as the thirteen hundreds. Fishing is a skilled and dangerous trade and in times before steam power and weather forecasts, men relied on their skill with sail and local knowledge of the weather, both handed down from father to son.

Colebrook’s the mineral water firm that nestled at the base of the cliff below the Hope Anchor Hotel brought the first steam trawlers to Rye, but despite having a steam engine aboard, the first vessel, RX1, was powered by sail, the engine was used just for winching the trawl back into the boat. It was a great improvement over hand trawling and much larger nets meant much larger catches could be landed with ease.

Today Rye fishermen have the luxury of powerful engines that propel the boats and haul the nets. They have amazing electrical devices that can tell them where the fish are and pinpoint their position to within a few feet. Despite all these improvements one thing remains the same. Fishermen still run the highest risks of dying at their work than any other profession. Firemen for instance are 23rd. in the ‘league table’ and policemen are 27th.

Since Britain joined the EEC the local fishermen have watched their income drop from a reasonable wage (if the risk was not taken into account) to a pittance. In the days before the European Economic Community Britain maintained a strict 12 mile nation limit on our shores, enforced by the Royal Navy. Fish stocks were conserved by adhering to mesh sizes which allowed the young fish to escape. The EEC scheme to preserve fish stocks was to limit the catch with quotas, it has not worked, more fish are being caught and thrown back for the gulls than brought back to Port. The whole system is ludicrous. Ask any fisherman which way he will vote if the promised referendum ever materialises.

The Wars Did Not Stop Them

Even in Wartime Rye fishermen put to sea to do their bit to feed the nation. Some died like the whole crew, save one, on another Colebrook boat the ‘Margaret’, blown out of the water by a mine in 1916. The Second World War took it’s toll too, Joe Hollands and Walter Longley were killed in Rye Bay when a German fighter strafed their boat the ‘Mispah’ as it trawled near Dungeness. Skipper Lock, although badly wounded, got the boat ashore at Jury’s Gap and went for help. The two dead men were returned to Rye in the Dustcart, an incident that was not condoned by the people of Rye. Mr. Lock was awarded the MBE for his act of bravery in trying to save his crew.

Another Rye boat, the ‘Dorothy Margaret’, owned by Jerry Bellhouse, took part in the Dunkirk evacuation. She, along with the Mispah, fished throughout the War and for many years after.

No article about fishing in this town would be complete without a mention of Harry Crampton. He had an amazing life, fishing from the age of 13 until his retirement. He spent many years after retirement relaxing in the Ypres Castle Inn and it is said he never had to buy a drink. His vast repetiore of fishing stories held other pubgoers spellbound. He was sought out for photographs and he was a favourite of artists, indeed a large oil painting of him adorned the walls of that famous establishment for many years. I wonder what happened to it?

Today Rye fishermen have their fine new Wharf at Simmons Quay, but are being forced out of the water by EEC quotas. Rye fishermen are tough, they have survived through worse than this, no doubt the Rye Fleet will still be trading their catch for years to come.

From Rye’s Own March 2008