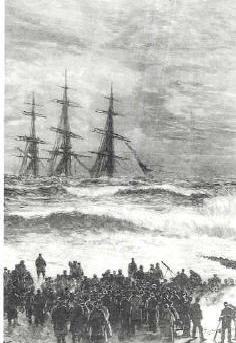

SHIPS IN TROUBLE IN RYE BAY AND OFF HASTINGS

On 11th November 1891 a powerful storm raged along the Kent / Sussex coast, wreaking havoc on Hythe, Rye and Hastings. Many ships got into difficulties and as the wind reached higher and higher speeds, rescue services and volunteers raced to aid vessels in difficulties along the south east coastline during the long, desperate hours of that fateful day and night. Such was the ferocity of the storm that shipping ran for shelter in Rye Bay, looking for protection from the high winds behind the Dungeness headland..

Henry Godbold, a photograper from Hastings went down to the beach with his camera to record the stricken ships. A large three-masted German barque named the “J. C. Pfluger” was driven ashore and became stranded on the beach at St Leonards. The ship’s twenty-four crew members were rescued by Coastguards using a line attached to a rocket (known as Breeches Buoy Rescue Equipment). During the same storm, a schooner named the “Nerissa”, which was on its way to Norway, was wrecked on Hastings beach. Henry James Godbold took photographs of both incidents and five days later later he registered the copyright of the photographs with The Stationers’ Company in London. The copyright registration forms describe the photographs as follows : 1/406/469 – “Photograph of a vessel (named the ‘J. C. Pfluger’) stranded at St Leonards-on-Sea, Nov 11th 1891, with rocket flying through the air to rescue the crew”. 1/406/470 – “Photograph of a vessel (named the ‘Nerissa’) wrecked at Hastings, Nov 11th 1891, showing sea breaking over her”.

The 1,000 ton JC Pfluger was later refloated and towed to Tilbury Docks, on the Thames.

SAD SCENE NEAR HYTHE

Two miles along the coast from Hythe the full rigged ship BEN VENUE (2033 tons), laden with a general cargo, and bound from London to Sydney, was proceeding down the Channel in charge of a tug; when off Sandgate she parted her cable tow-rope, and the vessel rapidly drifted ashore, This was about 6 a.m. when it was blowing a hurricane and a fearful sea was running. Seeing that his vessel was drifting ashore, the captain dropped anchor, but that was of no avail; the vessel struck and settled down hard on the bottom. The dropping of the anchor had, as it happened, a disastrous effect, and led to the whole of the ship’s company being imprisoned in the rigging for many hours, as the anchor had prevented her from drifting right inshore, where the crew could have been easily rescued. The seashore at Sandgate which was literally bestrewed with wreckage, was crowded with thousands of spectators throughout the greater part of the day. When the vessel sank the captain and crew took to the mizzen top, and here they remained huddled together from 6 o’clock, so close to shore that they could see everything which was going on, and yet unable to obtain help of any kind. The hull at low tide was several feet under water, and at high water her lower yards were about 20ft out. All her masts and spars were standing, but except those sails which were furled, every stitch has been blown away. The Sandgate coastguard were on duty from 4 a.m. and until dark continued the use of the rocket apparatus. A great number of rockets were fired, but from some cause or other every attempt failed. At midday MAJOR O’MALLEY and a party of no.52 Battery, Field Artillery, proceeded to the seashore with a 12-pounder breechloading field piece, and endeavoured by firing the gun to throw the rocket and line across the vessel, but the force of the discharge was so great in each case that the line was broken. From three o’clock no further attempts with the gun were made and the rocket apparatus was taken on to the foreshore and again used. The first shot was well aimed. Two of the figures were seen to emerge from the position in which they were huddled together and one man clambered down one of the ship-lines until he was almost wahed by the waves beneath him. Then some of the people were seen on the cross trees hauling; but after hauling some time the line proved to be broken. All the subsequent attempts were unsuccessful in reaching the ship. The poor fellow who discovered the rope appeared to have great difficulty in returning and was helped back by some of his ship-mates as soon as he got within their reach. A report was current to the effect that a man was washed ashore at Sandgate on a piece of wreckage, but before help could reach him, he lost his hold and was lost. Although thousands of anxious and willing hands were so near the vessel no help could reach the persons on board; the rockets fired all failed; and no lifeboat could be obtained. There was such a terrific sea running that it was imposible for any boat to approach the ship. The SANDGATE LIFEBOAT had capsized, and the DUNGERNESS and LITTLESTONE boats were engaged on other wrecks. A telegraph was despatched to Dover for assistance, and a gallant attempt was made in the face of a terrible sea to get the lifeboat off, the GRANVILLE TUG (Capt. LAMBERT) acting under the orders of Mr JAMES DURDEN, the Mr JAMES DURDEN taking the boat in tow. Upon reaching the Admiralty Pier it was found impossible to face the heavy seas, and both boats were driven away to the eastward, returning to the Harbour later in the afternoon. At night the greatest excitement prevailed on the seashore at Sandgate, and a crew was again mustered at Dover, and Mr DURDEN sent the lifeboat down in charge of the tug to make another attempt to rescue the crew.

The crew of the BEN VENUE were ultimately rescued by the SANDGATE LIFEBOAT at 9.50. A fresh crew was obtained about an hour previously, and after considerable delay in launching, the boat was got into the water precisely at nine o’clock. The rescue party was a scratch one made up of fishermen from Folkestone and some coastguards. She stuck to the beach for some time, but there were hundreds of willing hands at the ropes and behind her, and as she at last glided into the water a cheer was given by some thousands of voices. The lifeboat weathered one or two heavy seas, but within ten minutes she was alongside the wreck, and the work of rescue was begun. twenty-seven persons being saved, no women as was supposed being amongst them. The DOVER LIFEBOAT arrived in charge of a tug a few minutes afterwards, but too late to be of use. The shipwrecked crew was in the rigging exactly 16 hours.The enthusiasm at Sandgate, Folkestone and at Hythe when the men were landed was intense.

STATEMENTS BY SURVIVORS

The chief mate of the BEN VENUE (Mr SAMUEL WEBSTER) was interviewed by a reporter on Thursday morning at the Queen’s Hotel, where he was located with nine of his fellow survivors. His face bore a very haggered expression, and he stated that he lived at 33 Lindley Street, Sidney Street, London. The BENVENUE, which was an iron ship of 2,033 tons, left London on Tuesday morning with a general cargo for Sydney. They proceeded down channel in tow of a London tug, the name of which he could not recollect. All went well until they reached the South Foreland, when the wind blew very hard from the south-west. At nine o’clock the gale increased, and by the time they arrived off Sandgate the vessel became quite unmanageable. The wind was blowing a hurricane, and a fearful sea was running. It was a blinding storm. They deemed it advisable to drop both anchors, but even these with the assistance of the tug were not powerful enough to hold the vessel, and she drifted in towards the shore at Seabrook. When they were with a few hundred yards of the beach they heard a tremendous crash and concluded that the ship had struck. She commenced to sink at once, and in less than fifteen minutes she had disappeared beneath the waves. He did not attempt to lower boats, for a small boat could not possibly have lived in such a sea. As soon as he saw that the vessel was sinking he shouted to everyone to get up the rigging as quickly as they could, whilst he rushed below and fetched a rocket for the purpose of signalling for assistance. They all climbed up into the rigging and secured themselves as best they could, some of them got on the top sail yards, and secured themselves with lashings from the sails. They saw them trying to launch the lifeboat from the shore, but even if they had succeeded in getting out to them he did not believe they could have got off. Most of them thought it was all up with them when every attempt to rescue them failed, but he put his trust in the rigging and the mast for he knew they could never go until the vessel broke up altogether. Although they remained in such a perilous position for so many hours, and were well nigh exhausted they were somewhat comforted by being able to see the people on shore, and the attempts which were made to rescue them. It was a miraculous thing that they had not all drowned, and if the other poor fellows had done what he told them he believed that they would have been amongst them now. Immediately he saw the vessel was sinking he told them to get into the rigging and make themselves secure, but those who were drowned came down out of the rigging and were unable to get back again. It was too late. The vessel had gone too far down. He thought their idea originally must have been to jump overboard and swim to the shore, but that would have been quite impossible in such a boiling surf. Two apprentice boys, named BRUCE of Gravesend, and IRONMONGER of London, were drowned, also ARTHUR SWANAGE, the steward, CAPTAIN JAMES MODDREA, of Liverpool, and an able seaman named CHARLES WINTER. He (the chief mate) saw them all swimming with their life-belts with the exception of the captain, MR WEBSTER went on to say that when he came up from below with the rocket he saw the Captain and helped to get him into the rigging. Some of the men hauled him up with a rope, but when he looked round he saw that he had gone down again and went towards the cabin. As soon as he got to the cabin door the deck was under water. The hatches and deck began to burst up, and the force of the water running into the cabin carried the Captain in and he was seen no more. The vessel lay with six or seven feet of water above the decks. He saw the poor little fellow Bruce swimming about with blood trickling down his face. he thought the poor lad had been dashed against the side of the vessel. He also saw one of the men swimming towards the shore, and when he got about midway he saw him throw up his arms and disappear. Rockets were continually fired from the shore, but they were of no avail. Several of the men were struck by them. WM. DACEY received a severe wound on the hand, and EVAN EVANS was also struck on the hand and left arm. Several of them have marks of the rocket line across their face and hands and one man has a very severe cut in the face. The chief mate further stated that he had lost all his personal belongings to the value of £100. The rest of the men had lost their clothing and belongings, having nothing beyond what they stood in.

TWO SEAMEN DROWNED OFF DYMCHURCH

There were five hands on the Deal LUGGER SUCCESS, which was lost near Dymchurch. The boat was cruising for vessels requiring North Sea pilots, and was trying to hold to her anchor at Dungerness roadstead, when she was driven ashore. Three of the crew named ERRIDGE, FINNIS and BUTTRESS, succeeded in reaching the shore, but JOHN GRIGG (the master) and a man named PHILPOTT were drowned. Both men were married, and one leaves a family of four children.

This was one of the worst storms since the great storm of 1703 when many ships (many returning from helping the King of Spain fight the French in the War of the Spanish Succession) were wrecked, including HMS Resolution at Pevensey and on the Goodwin Sands, HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Northumberland, HMS Mary, and HMS Restoration, with about 1,500 seamen killed particularly on the Goodwins. Between 8,000 and 15,000 lives were lost overall. The first Eddystone Lighthouse was destroyed on 27 November 1703 (Old Style), killing six occupants, including its builder Henry Winstanley (John Rudyard was later contracted to build the second lighthouse on the site). The number of oak trees lost in the New Forest alone was 4,000.

On the Thames, around 700 ships were heaped together in the Pool of London, the section downstream from London Bridge. HMS Vanguard was wrecked at Chatham. HMS Association was blown from Harwich to Gothenburg in Sweden before way could be made back to England.

“Rye’s Own” February 2013

All articles, photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement.