Life as it was lived 50 years ago in a small village near Rye as seen by R. D. Symons of Silton, Sasks., Canada I grew up in hearing of the slow, country speech of the people of Sussex.

Only occasionally have I heard it over the past fifty and more years, for most of the English immigrants to the prairies come from the industrial areas of the Midlands and North of England.

After all, why should the Sussex folk have emigrated ? They had a moderate south-coast climate and were not crowded into slums and tenements. The grass of the Southdowns was green and turfy, smelling of wild thyme. The shepherd, the ploughman and the waggoner could all see the blue waters of the Channel, and beyond, the fair coast of France, from whence, in earlier days at least, came smuggled treats.

There was room to swing a cat. There were blossomed lanes in which courting sweethearts could linger. There could be a tasty rabbit for supper after a day at the plough-tail and a lunch eaten under a brier-grown hedge and yellowhammers piping for “a little bit of bread and no cheese.”

Why emigrate ?

For me it was different. My family followed arts and letters. They were Celtic-Norman; even if I (at least) was Sussex-born.

We had no farm, although we lived in a farmhouse. Nor would a farm ever be possible for me in this tidy land of few—if productive—acres, for my father only sold enough pictures to keep at bay the butcher and the baker and to provide an education for seven sons and two daughters

Stocks House

Stocks House was a typical East Sussex building of four hundred years ago, built in what is commonly called the Kentish style, with brick-floored kitchen, scullery and “wash-up”, as well as a bricked yard.

The usual great yew tree stood before it, for this was the site of an earlier building, of the time when all yeomen’s and country gentlemen’s residences (as well as most churchyards) could boast of one or more yews in their grounds.

These had not, however, been planted for adorn- ment, but rather to afford a supply of tough yew wood to make the bows which would uphold the honour of England at Crecy and Poitiers. The oak woods, too, had been left from the wild primeval weald-forest for a purpose. Sussex has always had one eye to the plough and one to the sea, so the trees were carefully harvested in bygone years, for oak built Britain’s bulwarks—the wooden walls from which Drake harassed the Dons and which later had bellowed at Trafalgar. Nor were oak and yew all the fee offered by Silly Sussex to the kings; for there had been iron-works too, famous in their time; when ash and beech, willow and chestnut and “apse” (aspen- )—but not oak—fell to the axes of the grimy-faced charcoal burners who earned their bread by supplying the smelters.

In my childhood oak was chiefly bid on by furniture makers, although at Rye a few small wooden ships were still being built by a dying race of craftsmen.

Elderberry Wine

Most of the big farmhouses had an orchard in attendance which, like the kitchen-garden, “Went with the house,” so in spite of the fact that our landlord farmed the land we were not without the fruits of harvest. Nor did we lack for wine, because on either side of the kitchen door as well as above the opening of the drain, had been planted strong, tall elderberry bushes, yielding a dark and juicy fruit.

In the overhanging elderberry bushes the blackbirds nested year by year. I knew, I saw, and I kept my peace, for our washerwoman’s son would rob a blackbird’s nest and feel proud that he had saved a few raspberries or strawberries.

If it was evening the carters would be watering their feather-footed Shire horses, and I would stand and watch the water gulping down their throats, and their ears flicking back and forth with each swallow, while the “soft spots” over their bony eye structures would contract and expand like bellows.

And so to the cart-shed below the threshing-floor of the barn. Here carts stood down-tilted on their red shafts. Here were the blue-painted wagons, wagons which had taken sacked corn (as all grain is called in Sussex) to Rye, and returned with linseed cake for the fattening bullocks, which stood knee deep in straw. Many a time had I seen these high-wheeled wains loaded high, the big horses scrabbling up Cadborough’ Hill, the carter, on foot, giving directions with his pointed whip and slow, hearty voice . . “Who-a! Come over, Varmer! Wey over there, do-ee, Cap’n!

Now, while these same horses munched hay in the brick stable, while Old Butchers sat to his cows, sending twin streams to thump in his pail, I would creep over and under the turnip carts and the wagons, scattering the speckled Sussex hens which had been dusting themselves on the dry, chaffy floor, or pecking about in the wagon-beds for scraps of Page Twenty-Nine cake, or running to glossy Chanticleer as he tuck-tucked over a new-found morsel.

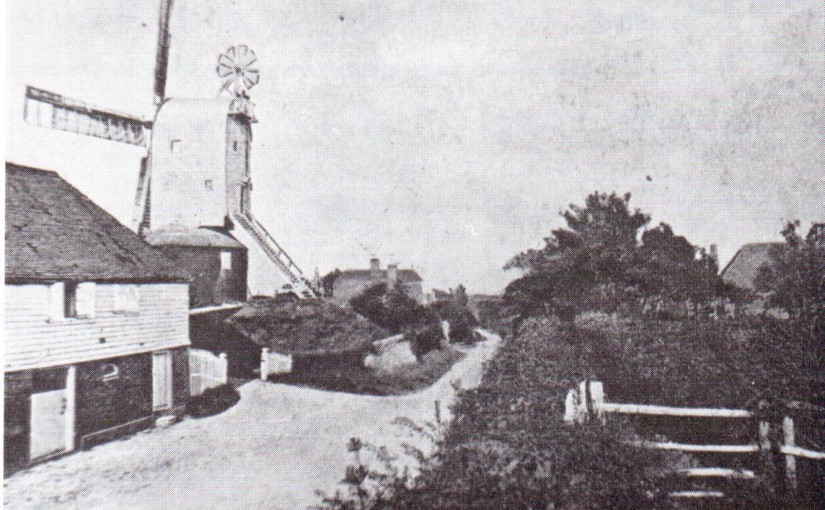

Udimore

The sun would be down and the bats fluttering and squeaking in the gloaming by the time Old Butchers took himself and his pails homeward and I turned towards the lighted windows of Stocks House, with something tight in my chest from seen and felt.

My bedroom faced on the rutted cart-track which led from the Hastings road to the farmyard. I always woke just before seven o’clock—or, rather, I was woken by the tramp of hob-nailed boots as the men came from their scattered cottages to their daily work.

I would hear, “Marnin’, Willum, it do be a fine day,” and the reply, “Marnin’, Garge. Yes, it be, ‘less them clouds be holding thunderplump.”

And… “Boy! Where’s that boy? Idunnamny times I do tell-ee muck out Cap’n fust!“

Or . . . “Ave-ce slop’ t’old sow, Edwin? She be main squealin’ ! .. . Oak! Liddle ‘uns already, be it ?

And I’d creep to the window to look down between the curtains upon the sturdy men with the strings holding up their corduroy trousers below their knees. And somehow envy them too, who had not to sit making maps of the world or declining Latin verbs. But never—no, never—did I hear from them an ugly oath or a besmirching word.

I loved the Land. I loved crops, cattle, horses. And so I came early to a wide and generous Dominion which offered me the land for nothing, so that these other things might be added to me, if only I cared to work.

I did care to work. But I missed the easy Sussex speech amid the cacophony of strange voices, some brittle, some sharp; often mouthing words I had never heard before.

Kaiser’s War

Then came the Kaiser’s War.

Once more, with Maple Leaves on my tunic, I saw Udimore village . . .I saw Stocks. I saw the ducks at the drain, saw the rooks winging their evening way to the churchyard elms.

But briefly. Briefly

And then it was France. And I was sent on a burial party. The dead were men of the Royal Sussex Regiment. They had gone into battle so young, these sons of Willum and Garge and Edwin. So young.

was first published in the April 1966

issue of Rye’s Own. The passing of

time has made it an even more sad

piece It brings home the sadness of

the terrible war of 1914-18 and the

stoical way the country people handled

their grief.

Udimore – Sussex

While back in Silly Sussex as ever was, shepherd met shepherd on the dawn-wet sheep paths all a-scent with downland mint, and greeted one another in the sober, quiet way of loss accepted.

They worked a little harder than usual, for work eases the pain of loss.

They still set their hens in the dark of the moon, still gathered their faggots by the evening light, still put the ‘taters to boil when they heard the whistle of the the Robertsbridge train at half-past eleven.

And the men still trudged to their cottages below the high-lifted shoulders of the downland, on the edge of the sheep marshes of the Tillingham and the Brede, and tried to smile at their women over the rabbit pie. But they said nowt . . . neither men nor women. For that is the way of Sussex folk. And Udimore and Icklesham rang out their sad yet hopeful bells, and Brede was close behind, and the answer came from Peasmarsh and Robertsbridge and Battle, where Saxon Harold fell on that Senlac day which brought the Norman speech to England.

And the lights in the little stone churches sent their beams to play with the swaying yew-boughs— the yews which had given the longbows for Agincourt, while the folks went quietly to their knees and prayed to the God of Saint Edmund. Going home in the dark, they could smell the wallflowers, they could feel the lift of the channel breeze, they could see the flash of guns lighting the sullen sky across the narrow water. But they said nowt.

All things come to an end and pass away. So did the war. And I came back to the land of meadowlarks and great sunsets and clean prairie winds, and I had my farm, my cattle, my crops.

But still I remember and am thankful. Remember as a man remembers his mother after his love has become his wife.

“Cinque Ports” April 2016

All articles, photographs, films and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2017 Cinque Ports Magazines Rye Ltd., Guinea Hall Lodge Sellindge TN25 6EG