Written In 1973 by Cristopher Davson

Let us take the bull by the horns. There is a love-hate relationship between Rye and Winchelsea. Such a relationship is most commonly found in families, and these two ancient towns are like rival sisters in a powerful family. Winchelsea, the elder, still beautiful in her widow’s weeds, looks down from a height of I20ft. on her still thriving somewhat vulgar sister, Rye. Rye looks up, from a scant 6Oft., at Winchelsea with a mixture of respect and – contempt is too strong a word indifference. Each town – for despite their small size both are indefinably yet indisputably towns not villages – ornaments and complements the other. Each derives its origin, identity, and purpose from its founding role, that of trade by sea. Trade, moreover, within that ancient compact of the Cinque Ports Confederation whereby the privilege, almost the monopoly, of trade from Seaford to the Wash was paid for not in taxes but in blood. This compact, originally struck in all probability by the Romans when they established the classis britannicus or “british fleet”, provided England’s only naval defence down to the time of King Henry VII.

Within the Federation the communities moved, with their privileges, as the harbours – themselves moved and their relative importance reflected the trade and ship building capacity which their harbour would support at any time. Rutupiae moved to Richborough and thence to Sandwich – still a Cinque Port. Anderida (Pevensey) shifted perhaps to Old Hastings, and then dwindled with the loss of Hastings harbour. The great storm of a 1287 destroyed Old Winchelsea, suffocated New Romney by removing its access to the sea and further exhausted poor Hastings, and made Rye and the promontory of Petit Higham the gateways to the new harbour of Rye Bay. Quick as a flash King Edward I, noted strategist that he was, offered Charters of Incorporation not only to Rye but to New Winchelsea which he was at pains to prepare and build. (The preparations for the building of the new town had in fact been commenced, at King Edward’s orders, in 1281.) Building lasted from 1288 to 1293 and the glory of New Winchelsea was to last another hundred years. Early in the 14th Century (1315) Winchelsea was admitted a full corporate member of the Cinque Ports Confederation with Rye following 20 years later. Both were described at that time as “Ancient Towns”. During the next 100 years, those of the Hundred Years War, both ports were in their prime and chief prosperity and one of the principal articles of trade was wine.

What was Old Winchelsea like? We don’t even know exactly where it was, save that it lies a mile or two offshore in Rye Bay over against Camber. But if we want to know what it looked like it is only necessary to travel to Yarmouth, a precisely similar settlement which has survived on its gravel ridge at the mouth of the Yare and which, appropriately, not only marked the Northern limit of the jurisdiction of the Cinque Ports Federation but actually belonged to them until the same King Edward I, as a boost to Yarmouth’s morale, transferred title to their land and management of their own affairs to the Borough of Yarmouth, leaving the Barons of the Cinque Ports only their increasingly nominal “rights” during the period of the annual Yarmouth Herring Fair. If you want to see Old Winchelsea, travel to Yarmouth. If you want to see the progenitor of New Winchelsea some say you must travel to Pompeii, since both in area and layout it is extraordinarily similar. For the town is laid out not like the circular or oblong British towns, descended from Celtic oppida, nor by straggling growth of Saxon and Medieval houses around some important crossroads. Instead it is firmly laid out as a gridiron of rectangles on the continental, indeed on the Roman pattern. How this came about we do not know; perhaps the chief architect of Winchelsea, Sir John de Kirkeby, Bishop of Ely, had travelled to Rome or had had a classical education. In any event Winchelsea is the first example of town planning in England since the Roman days. And the plan has survived absolutely unaltered.

What Was there, at New Winchelsea, before the new town? The Ancient Manor of Ihamme (Higham) stretched from Northiam (North Higham) to the present Winchelsea, taking in at one time Icklesham. In King Edward’s day the limestone promontory of Icklesham standing out into Pett Level was no more than a rabbit warren with a few windmills perched on top – one still survives (whose flour did they mill?). King Edward I bought in the necessary land, excised it from the parish of Icklesham, and conveyed it to the barons and freemen of Old Winchelsea for their new town.

The inhabitants were able to transfer over to their new plats, or plots, at nominal rents and set about building themselves new houses appropriate to their station according to the Royal Town Planning Regulations. We are fortunate to have a complete rent roll of 1292 of Winchelsea showing exactly who lived where. One or two of the descendants of the original inhabitants are still there. In addition to the inhabitants of the old town new immigrants came from the coastal ports and even a few gentry from London and further afield. Old Winchelsea is said to have been a town of some 700 households, a population of 3,000 to 4,000 persons (about the same as present day Rye). By the end of the 14th Century New Winchelsea had the same population as its ancient town, spaciously settled around 39 great squares intercepted by seven highways. Building started from the east and carried on far beyond Sandrock Hill, where the present Hastings Road takes off, to little lost New Gate standing lonely guard against Pett.

In the early 15th Century the sea retired from Winchelsea and with it the merchants. When in 1415 King Henry V collected together his great fleet for France and Agincourt his flagship, on which he himself sailed, was a Winchelsea boat, the Gabrielle de Winchelsea, but the fleet, significantly, assembled westwards at Porchester. By the middle of the 15th Century Bordeaux was lost, the harbour had gone, the wine trade had gone and the merchant population of Winchelsea had gone. In 1570, more than 100 years later, the townsmen petitioned Queen Elizabeth I for help in making a new channel from Winchelsea to the sea but Queen Bess came down herself to have a look, on the last day of her visit to Rye in 1573, and evidently decided that Winchelsea’s day was done. She praised (in Jeake’s words) the “goodly situation, ancient buildings, grave bearing of the Mayor and 12 Jurats in their scarlet gowns, and the city-like deportment of the people” and gave it the wry title of ‘Little London”. But she didn’t give them a new harbour.

With its trade and defensive purpose gone Winchelsea has survived as a sort of O.A.P. The situation is calm, healthy, and charming. People retire to Winchelsea. They have been doing that since the days of Queen Elizabeth I. At present the total population of those who live “on the hill”, is some 500, of whom for half it is only a second home. They are perhaps more than weekenders. In due course they will retire there. But the true permanent population of Winchelsea Town is perhaps some 250 persons. A tiny village with an average age, it is said, of 63, huddled in the ten easternmost squares of the original thirty-nine. Westward the sheep still, have Winchelsea, and doubtless a few rabbits. The Sunset Boulevard of Rye Bay. And more than this, it has an atmosphere, almost an extra dimension, of history.

The period of Winchelsea’s glory, the 14th Century, was the period of England’s greatest imperial power and influence until the reign of Queen Victoria. The almost total absence of any history for Winchelsea after the 15th Century makes it not only easier but more important to cast one’s mind back to those ancient days of chivalry and trade, of saints, monks, friars, crusaders, pilgrims, Jewish merchant bankers, and the constant nightly watch against French invasion. Nowhere else in England, today, can you live in the age of Froissart. Winchelsea dreams on her hill like an old dowager, looking down without envy, or pride, on bustling Rye, on the caravan and bungalow settlements of Winchelsea Beach, on the supertankers flogging up the Channel, without the slightest desire to join in.

Winchelsea’s Current Headaches We have already mentioned the “Clochemerle” affair, but that’s really only a pinprick. Winchelsea is shivering under two threats, both from East Sussex County Council (Highways Department). County want to close Strand Hill to all traffic so that they can remove the bump in the A.259 road at the Strand, where Strand Hill takes off so steeply, and improve the line of vision for the juggernauts so that they can aim at greater speed for the dangerous removed Ferry Hill. If this bump in the road was it would be impossible for vehicles to ascend Strand Hill. Winchelsea Townsmen are fighting this threat on three grounds. First, that it would leave only one access road to Winchelsea from the East. Winchelsea looks to Rye Fire Brigade and Ambulance Service in emergencies. It only needs a juggernaut to jack-knife on the Ferry Hill hairpin, blocking the road, to leave Winchelsea entirely cut off from services. Second, private cars, and the buses, use Strand Hill. It is estimated that maybe 40% of the through-traffic goes through the town and not round the back road. The latter is not only extremely dangerous, narrow and steep, with uncertain foundations, but is hard put to it at times to carry the present traffic of heavy vehicles. Why force more traffic on to an overstretched road.

Thirdly, they fear that Winchelsea’s few shops would suffer greatly, perhaps to the point of extinction, from the loss of any likelihood of casual traffic. Needless to say, there are no plans for a Winchelsea by-pass in the foreseeable future.

The second worry is something of a psychological malaise at the lack of young people and families. A town with no children is an eerie place. But the only remedy for this is to create employment once again in the town. Shall we see the Mayor and Corporation put forward proposals for an industrial estate in the parkland of Greyfriars? King Edward I would have thoroughly approved. The idea may be provocative but it isn’t as mad as it may seem.

Winchelsea has no dramatic skyline like Rye, it sits like a sort of leafy flat-iron on the Marsh and until you are up inside it the buildings are less evident than the trees. There are three ways to enter Winchelsea, by juggernaut, by car, or on foot. First the juggernaut; this must pass from Rye along the Strand to the vicious hairpin bend where Station and Udimore Road take off down to the Ferry, then’ up just grazing the Little Landgate to run straight down the back of Winchelsea southwards, most of which is now called Rectory Lane. Half way down, the Hastings Road bears sharply right down Sandrock Hill and the juggernauts are away. Apart from the roar of their engines and the fumes of their exhausts as they struggle up Ferry Hill and the speed (unrestricted) at which they whizz past the Old Rectory, they can pass through Winchelsea without ever noticing they have been in it. They may put at risk Winchelsea’s few children, there are supposed to be three at present, on the hill-crossing over to the playing fields or going for a walk to the old windmill, they may crowd into the verge local inhabitants on their way to Wesley’s old chapel, in which he preached one of his last sermons. They may frighten gatherings of the East Sussex Association for the Blind and other useful occupants of the New Hall. But they’re soon through Winchelsea.

The discerning motorist and the locals will enter more sedately up Strand Hill, leaving on the left the picturesque old Workhouse, once, it is said, a mediaeval brothel, now a Guest House and up for sale, and queue to negotiate the Strand Gate at the top of the hill. Immediately inside the Edwardian arch, less imposing than Rye’s Landgate, on the left is the little lookout terrace, like Rye’s Gun Garden, with a bench and a notable view over the Marsh and Levels. Immediately on the right Tower Cottage, formerly the residence for a few years of the actress Ellen Terry. On this terrace she and the great actor Sir Henry Irving might be seen a engaged in deep conversation or what-have-you. Many literary and dramatic notables must have visited her there.

Ahead lies the High Street, broad but not very long. Effectively it terminates at the New Inn. There are no street signs in Winchelsea nor are the houses numbered. They were all numbered and named in. 1292 and since then many people have had a go at changing them. It is probable that what now goes as the High Street was not in fact the original High Street but that this was the long street which runs the entire length of Winchelsea left at the New Inn from northwest to southeast and which bears among its names German Street, Monk’s Walk, The New Inn, Higham Green, etc., etc., etc.

Immediately left on entering High Street runs Rookery Lane leading down to one of Winchelsea’s few surviving great houses still in single private ownership, The Rookery or Cleveland. This is a charming lane with small half-timbered houses and a few Georgian ones on one side and gardens and a great view on the other. On the right of the High Street runs Barrack Square, the heart of Old Winchelsea and its old inhabitants. Winchelsea’s squares have mostly been filled in with buildings and private gardens so that they are not easily recognisable as squares, with the exception of Church Square where St. Thomas’s stands spaciously in the great churchyard. But Barrack Square was the military quarter of the town and on its west side are the remains of the 19th centuryand earlier-cavalry barracks, whilst in the midst of the Square stands the magazine and out at the other side on Castle Street is the old armoury, one of the few stone houses of Edwardian times to survive, much restored.

At the back of Barrack Square stands a small cluster of Council houses known as Spring Steps and here are to be found the descendants of the original Winchelsea folk. Behind Spring Steps a steep flight of steps lead down to St. Catherine’s Well, some 50 ft. above the main road, where a refreshing supply of cool water still runs. This was one of the principal sources of water for the town from the time of its foundation. Moving up the High Street to the next intersection Castle Street, to the right, takes its name from the Castle Inn, one of Winchelsea’s two pubs. Here Jack Marchant from Camber, looks after the visitors.

Opposite the Castle Inn by the Armoury stands the Town Well with quaint regulations still enforced by the Mayor up to 1910. Across the corner between the well and the High Street stands a fine old residence Periteau House, which recollects the efforts in the I8th. Century of some Huguenots who attempted to revive trade in the town by establishing cambric manufactories. (The other large house of similar and origin is Mariteau House in German Street opposite the Trojan (or Jews) Plat Council Houses.

Mariteau House came, at the turn of the century, into the hands of Lord Ritchie of Dundee, whose family are still ornaments of Rye and Northiam.

Mariteau House

The cambric trade did not flourish and Periteau House came in due course in the late 19th Century into the hands of Dr. Ernest Skinner. It was at this time that the house acquired its local nickname of “Dizzy House” because Dr. Skinner ran this house, and a number of other houses in the town as select private mental homes and the well-heeled but dimwitted inmates became a familiar sight as they were led by their attendants around the streets.

The Town Wets

Continuing down German Street across the High Street into Higham Green and turning right into Mill Road we come to one of Winchelsea’s two tearooms (the other is in the High Street near the Post Office). This is Manna Plat, which boasts, in addition to a fine reputation for teas, a splendid example of the typical 13th Century Winchelsea wine cellar, now in use as an Art Gallery. In its heyday Winchelsea must have had hundreds of thousands of gallons of what a contemporary writer describes as the “joyous juice” of claret, not to mention brandy and sack, in these cool bonded warehouses. There would be room to store all that the 18th Century smugglers could import and much, much more. In later years some of these cellars were put to a most ignoble use, continuing until the present century; they were used as domestic cesspits with the family latrines positioned over them and they would only be cleaned out every ten years or so. The mind boggles at the stench.

Space does not permit us to write of St. Thomas’ Church which is the next great object to meet the eye. Every visitor to Winchelsea will naturally look over it, and if he is wise will buy the excellent church pamphlet. Everyone knows that the Church, like Winchelsea itself, is unfinished but what is left is a moving and powerful fragment: It is around this churchyard that the great “Clochemerle” battle is still raging. The town is deeply split on this absurd issue, certain parties maintaining with truly patrician hauteur that visitors should “acquire greater self-control over their natural functions”, others that if it must be done it should be done somewhere else – for example “down beyond the Council houses” – while the moderates, including the Rector, feel that Church lands have always been at the people’s service and should be no less so today. Meantime Jack Marchant at the Castle Inn kindly throws open his establishment to travellers taken short.

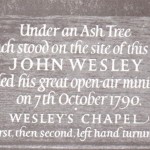

At the foot of the west end of the Church stands Wesley’s tree or rather the successor to the tree under which John Wesley preached his last great open-air sermon. But to get the feel of early Methodism you should continue across the High Street past the New Inn and turning left into Rectory Lane you will find the humble door of the converted cottage in which Wesley’s first preaching house was established. This has been beautifully restored by the Methodist flock in Winchelsea, with outside donations, and gives a splendid impression of the intimate piety of the days of the great reformer. It is not hard to imagine the old gentleman in the pulpit himself.

Continuing along Rectory Lane we pass the New Hall, built some 40 years ago, which provides, despite financial difficulties, some sort of social focus for the community. Beyond this, on the site of John Wesley Preached Here the old church of St. Giles, stands the Old Rectory, now being restored, where the new owners hope to develop and build additional houses between it and the road. A creepy spot this, for terrible deeds during the days of the French invasions took place here and it is not for nothing that the little lane leading off to the right, now called Hogtrough Lane, is better known locally as Deadmans Lane. On top of the bodies of the victims of the French attacks the bodies of the victims of the Black Death were soon to be piled. A sad corner of Winchelsea.

Beyond the Old Rectory lies Backfields, where lived Doctor Jack Skinner, brother to Dr. Ernest of “Dizzy” House. Dr. Jack was physician and surgeon to Winchelsea and Leslie Whiting’s father remembered being treated by the old gentleman, before he removed to Mountsfield, Rye. Apart from fearsome doses, he would perform minor amputations and whatever might be needful. They had to be a self-reliant lot.

Near the windmill on the meadow slopes west of the town on the highest point stood the little church of St. Leonards, about which there is a curious history. St. Leonard was the St. George of Sussex, that is to say his speciality was killing dragons. Indeed he did for Sussex as much as St. Patrick did for Ireland, his principal activities being in St. Leonards Forest.

He also gave us St. Leonards by Hastings, and it is to the Borough of Hastings that the little parish of St. Leonards, New Winchelsea, belonged. King Edward I did not excise from its parent body and deliver it to the new town hall with all the rest so it survived, a small alien fragment, in the new town until recently. St. Leonard also had magical powers over the winds and the waves and it is said that the monks collected many thank-offerings from the hopeful relatives of seafarers, by using a long spindle to turn the weathercock on top of the steeple to the point of the wind for which the devout were praying to ensure a favourable breeze for their loved ones-thus producing instant answers to prayer. The tale about the “rigged” weathercock is probably as unreliable as the tales about the dragons.

If we continue the lull length of Rectory Lane and turn back to Winchelsea to resume the main line of German Street we carry on through orchards and pasture until after a few small twists the headland on which Winchelsea stands suddenly narrows in and at the very tip comes the great surprise, New Gate. The original town walls started here and ran all around the town, with a ditch, where the cliffs did not give sufficient protection. They cannot have been very strong or stout walls since little trace survives. This being England, “New Gate” is at least 600 years old. Here is another well, but the town deserted this corner early and it was the principal paint of entry for the French invaders. There are a glorious views over to Icklesham and Fairlight whilst in the foreground lurks the ancient Wickham.

Returning down German Street we turn down the right-hand side of Church Square (Back Lane) and as we cross Thomas Street we see on the left corner opposite one of the oldest houses in Winchelsea, Glebe House. Here lived Dr. Martineau – the celebrated 18th Century pharmacist. Down by the entrance to Greyfriars stands the new St. Thomas Church of England Primary School, which caters for Winchelsea Town’s handful of children and a much larger population from Winchelsea Beach. A beautiful, and beautifully situated, little primary school this. Was it selfishness to put the school so far away from the children it served? But Winchelsea would indeed be a sad place if there were no children’s voices to be heard in it.

On the left at the road runs St. Thomas Road at the back of the Church with the Rectory on the site of the old church school. The road continues as Friars Road through increasingly charming houses to the gateway of “The Friars” or Greyfriars, site of the old Monastery and now a County Old People’s Home. In the grounds, visible on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, are the splendid ruins of the Chapel of the Virgin Mary. This was another of the Great Houses of Winchelsea formerly in the possession of the Stileman family, then of Lord Blaneborough, and now of the old folk.

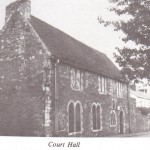

Returning to the crossroads of German and High Street, the New Inn and St. Thomas’ Church, we reach the centre of Winchelsea which we have deliberately left to last. Here stands the ancient Court Hall. The Court Hall, together with the three town gates and the town well, still belong to the Mayor and Corporation of Winchelsea, who are still appointed under the Charter of 1292 granted by King Edward I. Winchelsea Corporation was not abolished by the 1880 Municipal Corporations Act, nor by the great Reform Act, nor by the Local Government Act 1972. True they have lost all their powers but they survive as a Corporation with their rights and privileges. Rye Corporation, also incorporated by King Edward I, will be abolished for ever in April 1974. But the Mayor and Jurats of Winchelsea will go on. They are a self-perpetuating oligarchy. The Freemen of Winchelsea elect others among themselves from time to time to make their number up to twelve, and those twelve take it in turn to bear the mayoralty. A Freeman is a Freeman for life. Because the Freedom of Winchelsea nowadays is primarily the freedom to dip into one’s private pocket for public purposes, it is natural that not very many aspire to this honour and that those who do so are mostly well-to-do retired newcomers. Mr. F. A. Inderwick, Q.C., Mayor of Winchelsea in the nineties, was such a man, and only a part-time resident in Winchelsea – at Mariteau House. He was also Rye’s first Honorary Freeman. Today’s Mayor is a newcomer, Mr. Clarke. The Corporation’s only income comes from a few tiny dues, and from the Museum which occupies the upper part of the Court Hall. Here the Mayor is duly elected on Mayoring Day (Easter Monday) but here until the last century he also held his judicial court with the town “clink” below him and the prisoners brought up for sentencing and taken down, sometimes for execution. Like the other Cinque Ports Mayors he had powers even of capital punishment.

The Court Hall is a Very Fine Medieval Building

Some authorities think that it is older than the Edwardian town and that the present structure is in fact the old courthouse of Icklesham Manor. We must leave this to the learned. But the Museum is well worth a visit and also the clink below which now doubles as a boys’ club and as the Public Library. It’s all on a small scale but so is Winchelsea nowadays.

We have mentioned Winchelsea’s two inns. There is also a Post Office, a couple of general stores, a butcher’s, and Barlings the Grocers. The latter is one of the oldest shops in Winchelsea (in Highams Green on the way to Manna Plat). Of employment opportunities in the town there are virtually none. There are one or two small firms of builders who are kept busy adapting and renovating the old houses for the newcomers, now dividing a house, now reuniting it. There is still work available for jobbing gardeners, and the gardens of the great houses used to employ many full-time gardeners in the old days.

The Little House in Friar’s Road was built in imitation of an old “colonial house” by General Prescott on his retirement as the first Governor General of Canada. The plaque on the house commemorating the writer Ford Maddox Ford was unveiled some years back by Labour Peer Lord Soskice, a descendant of Ford Maddox Ford’s. Henry James and Rudyard Kipling were visitors to this house, and many members of the Arnold Bennett set. Winchelsea has links too, with George Bernard Shaw although there is no evidence that he ever came to Winchelsea, since his devoted secretary Blanche Patch, author of “My Thirty Years with G.B.S.”, was the daughter and grand-daughter of Rectors of Winchelsea.

Writers have come to Winchelsea. Thackeray, Joseph Conrad, Ford Maddox Ford – the last two lived in the little house in Friary Road. None of them seem to stay very long.

Sir John Millais came to Winchelsea and painted one or two pictures of which it forms a background, and his grandson is now one of Winchelsea’s more venerable inhabitants. It is hard to imagine that this peaceful sanctuary for elderly and well-to-do pensioners was once a busy, noisy manufacturing market town, more like Aldgate High Street even than Rye High Street. Armed men, sailors from all parts, pilgrims, Jews, traders, shipwrights, craftsmen, merchants. Is Winchelsea haunted? A visitor wouldn’t know, and a local wouldn’t tell.

“Cinque Ports” April 2016

All articles, photographs, films and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2017 Cinque Ports Magazines Rye Ltd., Guinea Hall Lodge Sellindge TN25 6EG