The Pubs of Rye no. 2.

The Union Inn East Street.

By David Russell.

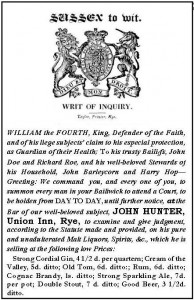

The Union Inn which recently closed has joined the ranks of the ‘Lost Pubs’ of Rye. The building was originally two 16th century cottages and a small shop. The cottages may have been licensed centuries ago, but by the 19th century the building was owned by John Swain and occupied by his under tenant John Hunter, who converted one of the cottages into the Union beer house in 1830.

John Hunter was keen to become fully licensed, and applied annually over the next three years. His application was granted in 1833 and he became ‘a fully licensed man’.

However, a full licence did not guarantee immediate success, and for some years he also worked as a self-employed tailor during the day while his wife Sarah ran the pub. John Hunter died in 1839, after which the licence was transferred to his widow.

In 1841 the pub was sold, and a deed tells us that: ‘John Hunter, landlord and under tenant of John Swain, sometime since converted these premises into a public house bearing the sign of the Union Inn’.

A valuation of the property in 1861 shows the licence was then held by their son James and thus, for 30 years the pub was run, but not owned, by the Hunter family. The valuation describes the Union at that time as a very small house, with only one public room separated into a bar and a bar parlour by a partition.

The valuation lists one bedroom but no accommodation for letting. It had a kitchen and wash house at the rear of the building and was attached to a small shop next door previously used by John Hunter as a tailoring shop. At some later date the pub was enlarged when the two cottages and the shop were integrated.

The valuation tells us that the bar parlour had seats fixed to the floor, shelving behind the bar and a zinc blind on two brass rods. Among the bar equipment was a ‘spirit fountain’, some ceramic spirit barrels with taps and fittings, a beer engine, another zinc blind and four stout metal bars supporting the partition.

Beer was only pulled in the bar, and parlour customers were served through a serving hatch in the partition. All tables and seats were fixed to the walls or the floor, and the bedroom was furnished with plain deal furniture.

The shop was basic with only a counter and shelving listed. However, the valuation points out with some pride, that ‘the pub sign was made of wrought iron,and was the first class work of a local blacksmith’.

The Union never had a tap room, suggesting perhaps that the landlord was trying to move away from the beer house image, and seeking custom further up the social scale.

In the same year, 1861, the next landlord John Paine Munn was charged with having the pub open for the sale of beer at 1.30am on a Sunday morning and for refusing to admit the police. When a constable was finally admitted at ten minutes to two he found two drunks in the bar. Munn claimed they were lodgers and, as the law then stood, lodgers could be served at anytime. However, as the pub had only one bedroom we can assume they were not genuine lodgers.

In 1864 landlord Henry Baldwin suddenly gave up the licence, and it was felt that the Union might close if a new licensee was not quickly found. George Austin stepped in around September and took over the Union licence for a few months ‘to ensure the continuity of this public house’, i.e. to ensure it stayed open. This was one of few instances in Rye when the magistrates allowed an individual to hold more than one licence concurrently. Austin was followed in December 1864 by Henry Huckstepp, who gave up the licence of the George Tap to run the Union which he saw as a small step up the social scale.

By the late 1860s the Union was popular with local fishermen and boat owners. This patronage was reflected in the fact that a number of Coroner’s Inquests into accidents and deaths in the fishing industry were held here. The local bench also felt that fishermen who might be required to attend and participate in these inquests would be more comfortable in the Union than in the more formal surroundings of say, the Red Lion or the George.

Nevertheless, members of inquests were often required to inspect the body which was laid out in the pub. It was the local custom for members of Coroner’s Inquests to adjourn to another pub after such a gruelling and harrowing experience. In the case of the Union, jurors usually went to the George Tap.

A typical inquest into the drowning of a fisherman in Rye Harbour, in 1881, was held in the Union Inn in May of that year, but failed to come to any conclusion as to how the ‘accident’ had happened. They could only agree that the deceased was ‘found drowned in Rye Harbour’.

In the 1930s the Union became a ‘Goth pub’ when it was acquired by the People’s Refreshment House Association Ltd, a temperance organisation influenced by the ‘Gothenburg Model’ of ‘disinterested management’ founded in Sweden. The manager of the Union was described as an ‘agent in the cause of temperance and good behaviour’, was paid a fixed salary plus any profit from food and non-alcoholic drinks. All profits from alcohol were donated to local ‘objects of public utility’. A few ‘Goth pubs’ still exist in Scotland but as far as I know the Union Inn was the only ‘Goth pub’ in Rye.

More recently the Union was a contender for most haunted pub in Rye and could boast three different ghosts. One ghost who resided there was apparently that of a young unmarried mother who died after being pushed down the cellar steps in the 1850s. In 1993 researchers into spiritual phenomena witnessed banging and laser flashes, and the kitchen door opening and closing by itself.

Further investigations revealed that the landlord’s young son had been visited by the ghost of ‘Postman Pat’ at night, and that several others staying overnight had experienced the ghost of a seaman in a blue jacket sometimes wearing a sou’wester. The old lady next door also experienced the seaman in her attic. We can only ask: Was this the ghost of an old smuggler moving contraband between the attics, or perhaps of the fisherman who drowned in the harbour in 1881?

Downstairs, the ghost of Emily, a young woman in a red dress, was often seen walking through the bar towards the cellar steps. She apparently died from a broken neck after being pushed down the cellar steps when pregnant. According to the Ghost Club investigators, Emily and her family lived in the middle cottage in 1856, and her father, a local mortician, was apparently ashamed of her pregnancy. However, when the investigators made contact with the ghost of Emily in 1992, she denied the baby was hers. The baby’s remains were/are allegedly contained behind a glass brick in the rear dining room. The pub was reputably rid of its ghosts in 1993 when exorcists rebalanced the pubs hidden ley-lines with a row of nine crystals.

The Union was listed Grade 2 in 1951, including the projecting shop window with small square panes at the north corner, dating from the early 19th century.

From The Pubs of Rye, East Sussex 1750–1950 by David Russell.

This book, illustrated with around 100 photographs, is in paperback, published October 2012, 282 pages, price

£13..99.

It can be purchased at Martello Bookshop, Adams of Rye, Rye Tourism Information Centre, Rye Heritage Centre and Waterstones in Hastings. It is also available at www.hastingspubhistory.com, by email: [email protected] or phone 01424 200227.

By David Russell.

“Rye’s Own” February 2013

All articles,photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement.