The Conclusion of Clifford Bloomields Wartime Recollections from Jo@ Kirkhams Rye Memories Series

I am able to give my reader some idea of the events that we, in Rye, were witnessing as I should spend many an hour sitting on the flat shed roof in our garden – on the fine summer evenings and weekends of July and August 1944, waiting and watching for the guns to go into action – at times looking towards the gunsite beyond the end of the houses in our road, some 300 yards away.

Suddenly and silently the gun barrels would elevate just a little, and instantly commence firing. The roar of the guns was really deafening, not only these guns, but every gun in the vicinity.

Away on the horizon there was nothing to mar my view. I would see the little black puffs of exploding shells and, by now, the noise engulfed the mind. The interest now was to watch the distant action, as the 3.7 inch (9.4cm) calibre guns would each be pumping out shells at the rate of 25 a minute.

Multiply this by eight, and then by the rest of the heavy guns, and add the various assortment of smaller guns, (the 40mm Bofors output was 120 shells a minute) and finally, if this wasn’t enough, and the searing noise of the Z battery rocket launchers by the Martello Tower at Rye Harbour. Rockets could be fired at the rate of 9 in 3/4 of a second) and this may give you some idea of the noise the barrage created.

The puffs, now tightly packed together, would form a black cloud rapidly coming closer, growing at the speed of the unseen bomb, probably at 350 miles per hour. The cloud was like a great monster – an elongated column of black smoke, beginning to thin, turning grey and drifting out on the horizon. Its length could now be 3 miles long.

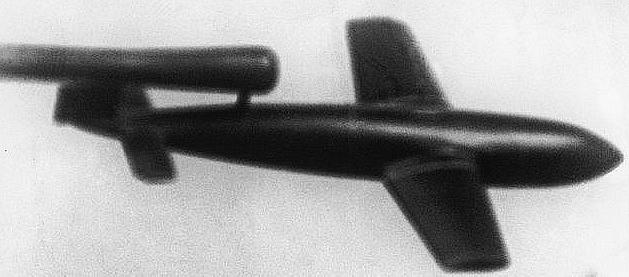

I was looking all the time to see the speeding bomb, and then seeing it plainly coming into view, just keeping ahead of the exploding shell bursts. The sound of the bombs ram jet engine was completely drowned by the barrage, and then suddenly there was a large ball of fire. More black smoke and the pieces of debris from the disintegrating flying bomb burst out of the fire ball. Instantly the guns would cease and then there was incredible silence.

But it was common enough to find 2 or 3 more bombs speeding land ward, ahead of their exploding smoke trails, yet to be annihilated.

All gunfire would generally cease once a bomb was over the built up areas of the town, but I’m not sure that that was the reason, or whether it was because the landward limit of the gun belt had been reached. There were times that when a bomb was approaching overhead, it was a case of “run for cover” – standing in doorways as the sound of schrapnel was plainly heard tinkling on the roofs, pavements, and roads. Probably because the gun crews were becoming a little exuberant so as not to let the bomb escape. I do not ever recall anyone being injured by falling debris, but it was very possible.

Imagine this repeated in the darkness of the blackout, standing, as I have done many times, in the bedroom window, watching the greatest firework display ever – tracer shells arching up from all directions on the ground, to the little flaming points of light speeding through the sky towards Rye – then almost always a ball of fire – and then it was all over.

As the day passed into August, the flying bombs were becoming more numerous, but the guns were also becoming more accurate. Only a small percentage were getting through the defence line.

At work on the Marsh, it could be very scary at times as there was nowhere to take shelter other than under the odd farm crossing bridge, or lying within the banks of a ditch, not that this gave much shelter. It was now becoming very common to find, anywhere on the Marsh, the little black plastic shell nose cones, history now tells us that the reason for accuracy by gun crews was that the shells were now fitted with a new proximity fuse in the nose cap.

It was said by locals generally, “If only the Londoners could see the success the gun crews were having!” The news bulletins on the radio made very little reference to flying bomb activity, so as not to let the enemy know what effect they were having.

A very unfortunate incident occurred on the Blue House, Brookland gun site. A bomb, disabled by gun fire (a rare event as they were usually destroyed), actually crashed and exploded amid the tented area of the gun crews, killing and wounding a number of soldiers and A.T.S girls.

To cater for the hundred of men and women of the Royal Artillery, two very large marquees were erected on the Cricket Salts, parallel to New Road – one a N.A.A.F.I (Navy, Army, Air Force, Institute) canteen and the other a type of concert hall, run by an organisation known as E.N.S.A (Entertainments National Service Association). We teenagers would find our way in by crawling under the canvas sides when shows were in progress. These facilities were to give some light relief to the weary gun crews who were manning the guns 24 hours a day.

By late August, the British forces were advancing across northern France, over-running the flying bomb sites. It is very possible that even some of the army divisions that had been stationed in Rye, were now doing this.

September/October/November 1944

Our danger was now rapidly passing – the last flying bomb that I recorded was on August 30th. No more were seen and the guns remained for a few weeks and then were cleared. During this period, the site crew at Rye Harbour Road stacked all their empty brass cartridge cases on the roadside to await collection. It is no exaggeration to say they were in stacks, mostly in boxes, 6 feet or more high and roughly 100 yards long in two blocks. I passed them a number of times and thought I must have one for a souvenir, so during one dark evening, I cycled there, armed with a sack, and took one. I was rather taken aback by the weight and it was 4” (100 mm) in diameter and 3’ (1m) high, when standing on end. It remained in our shed for a number of years and then I took it to the Camber side of Rye Harbour and hung it up there, to be used as a gong to call the ferryman.

Call Up

September/October/November 1944 These months were uneventful, as far as war was concerned in Rye, but not for me. I received my call-up papers to report to Preston Barracks, Brighton, for a military service medical. I wanted to join the RAF, but at this time, due to the late stage of the war, recruiting was only for the army. There was also a chance I might be drawn in a National Lottery for service in the coal mines, whose winners were known as Bevin Boys.

But luck was with me, for on the day my final call up came, it read “Report to Cardington, Bedfordshire”. A very few days after my 18th Birthday – November 30th – I was in the Royal air Force.

Therefore I did not witness the end of hostilities and the celebrations, if any, in Rye on V E Day.

From Rye’s Own October 2003

All articles, photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement.