By Arthur Woodgate

Having left school there was no more thought of hops (except one could not help seeing them everywhere), for some years, then in the thirties I was asked by the then foreman of the Stuart May hop and fruit estate, to build two brick coppers at crutches farm, Icklesham. The foreman, Stan Brewis, said I could work for them then, for a couple of months. I was amongst the hops again, and (apart from the state demanding two years). Those 2 months turned into 19 years of looking after the Stuart May estate buildings at Crutches Icklesham, Sharvels Peasmarsh and Iden Lock Farm and eventually took over from Stan Brewis; when he left; of being in charge with a staff of five, and power to engage casuals. “Sharvels” was headquarters and we had responsibility for all the buildings on the estate but am dealing only with those to do with hops here will describe other aspects later. We had a store and workshop at Flackley Ash, Peasmarsh. We had to keep the hop bins in good repair, so that made an excellent place to do some of them in bad weather. I knew my counterpart at the much bigger hop undertaking at Bodiam, who, although still in Sussex, used Kent pattern bins. It was only when they asked to borrow some of our bins that I found this out and when I had occasion to travel through that other great hop county of Herefordshire there was yet another pattern around.

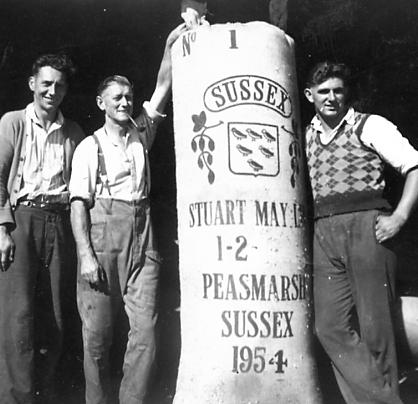

George Fisher; Alec Murrell (Dryer); Jimmy Paine

Sharvels had other interests, but hops are the subject here. Maybe we can look at the other interesting matters later. The oast house kilns were getting old and needed constant attention. Tapered oast tiles were not easy to obtain so one had to cut square ones to shape and the only way of doing that then was with a pair of pincers (no power cutters then) and the back of your hand could swell up and ache for days.

One of the funniest and somewhat frightening experiences was being at the top of a ladder when the arm of the oast cowl swings round just above your head. Taking a cowl off, before the days of site cranes, was far from easy. The stump is about four feet (sorry youngsters can’t work it out in millimetres) down inside the roof, so a long pole had to be put up through the open side of the cowl with a pulley block and rope high enough up to clear the roof and stump and point. Three or four guide ropes had to be fixed to the cowl itself so that helpers could keep it away from the roof and walls as it was lowered down.

Inside the roof was lined with lath and plaster which was prone to decay. We had to make sure all these things were in first class condition by the last Thursday in August; a day I always had in my mind and have not forgotten even now. It was then that the hop drier (in our case Alec Merrel) moved into a little room in the oast building and put the pans in which a fumigating powder would be put so that when set alight it would send a fume up through the hops when they were drying on the ‘hair’ (openwork floor covered by a hair carpet) above and lit the fire to warm it up ready for the first load of hops on Monday morning. At the same time pickers would be moving into the 52 hopper huts we had in Sharvels yard and a scene of activity continued throughout the hopping period.

Top: Fred Lancaster dealing with rubbish from new Hop Picking Machine

1954.

Centre: Joan Beaney (Bailiffs Daughter) off for another load

Bottom: First operators new Hop Picking Machine, Sharvels 1954.

Bonfires, on which they cooked their food, cropped up by each hut. Lovely sight and smell from 1935 onwards. Jempsons would have supplied them with bread and no doubt the “Cock Inn” (from always it seemed) with beer and entertainment. I don’t quite remember this. But I am told that horse dealings used to go on at weekends. It was an exiting time what a pity it has all gone, and in a way its a pity horses are dying out, but I remember when Sharvels had six lovely Shire horses still bringing in the hops. (I hope to deal with the horses again other than with hops). However tractor trailers were gradually taking over.

There must have been a great demand for hops at that time, some 25 years or so before the decline and collapse of the industry, because we were given the job of building two new kilns on the oast and a new drying plant was installed to serve all four hairs, the new ones were square with louvre ventilation instead of cowls, but it had to have a four feet square chimney forty feet tall. As I walked down from Flackley Ash to Sharvels, with the then owner, Stuart May, he looked at the chimney and then at me and said, “can you put another 10 feet on top of that ?” I replied that I could if he got me some scaffolding, in a few days, a then modern scaffold was put round it, so up we went, and , as is the case of such narrow and tall structures, it swayed about a bit, so I would allow no one else up for fear we got out of step and did some damage, all the bricks and mortar were pulled up from the ground and I unloaded them myself, however, when it came to putting an iron collar round it, I had to have some help and we had to be extremely careful.

We finished it quite safely and it stayed there until someone pulled it down and turned the oast into a dwelling, in common with all other oasts in the district. During the chimney hiring I invited Stuart May to come up and look at his estate in one sighting as it was a lovely view, but he said he could see enough from the ground. As I get older I can understand what he meant. Dryer Alec Murrell grumbled because the extra height sharpened the draft from his fire requiring him to adjust his dampers and he had to use more fuel to keep his proper drying heat.

Like other industries hop growing moved on in the 1950s. Picking machines were being thought about and the hop poles were being replaced by wire work and string. Alec, who was in charge of the whole hop process; not just the drying; and his colleagues used stilts to fix up the top of the wires where the string passed through, but long poles with a piece of pipe at the top were made like long needles so the operatives with the ball of string on their backs could pass some over the top hook and then pass it under the bottom hook, one had to look out when they brought the needle pole down as it shot quickly out behind them. An Army of workers still had to treat the bines and train them up the strings, not allowing more than five strings to a pole as they did before hand picking was replaced by machines, after which the large Army of people earning some extra income for the winter became a mere trickle of regular employees.

Sharvels was one of the first Peasmarsh farms to install a machine so my little gang had to get well involved. We had to put the concrete cubes in the ground to act as foundations for the steel stanchions to stand onto hold the steel and asbestos shed for the machine which was some seventy foot long, and quite wide and it had to have a concrete floor all round to allow tractors to show around, so it was a rather big shed. Two walls had to be built about four feet down, so that when the machine was mounted on them it formed an inspection tunnel. This inspection in the early days and the clearance of leaves was a dangerous job, and although there were many emergency buttons to stop the machine, and safety tools were around, we did hear that on a neighbouring farm, a man lost an arm whilst working in the tunnel. The horses had by now, been replaced by tractor towed trailers. With gantries rigged on there so that the hops could be brought in hanging upright as they had grown. Then they were transferred to hooks on a conveyor belt on the machine and were being dealt with as they went round. They were quite a sinister sight, all the hops and leaves were stripped off. The hops going one way and the leaves another.

The bines and string together with the leaves were passed out to one side where Fred Lancaster, who used to be in charge of the horses, was waiting to deal with it. Eventually the hops passed along a wide conveyor belt, with ladies lined up each side to pick out the rubbish and any odd leaves that might have got by the extractor, they were then caught in pokes and put on yet another moving belt which took them up to the stairs to be dried and spread out just below Alec’s knees. When dried to his satisfaction they were pushed out on to the cooling floor with wooden shovels. They called these “Scrumits” (at least that is what it sounded like, but can’t find it in print anywhere or anybody who can spell it). In the cooling room there was a round hole with a press over the top. Hop pockets were fitted into the hole and hops pushed down into them, and then a press let down on them; in hand picking days this was operated by turning a handle by hand, but with the coming of the machine picking, also came the electric operated drying machines. Alec would watch and operate the press from time to time, until a weight of 1 cwt.-2 quarters was reachable a target, one or two extra pounds were allowed, but it was frowned on, so a hop dryers job was highly skilled, and I don’t suppose ever paid enough for. Taken off the press the end of the pockets were sewn up, and added to those in store in the room below the cooling floor to wait to be taken to the hop auction in London, run by the Hop Board who sent round samplers to cut small cubes about six inches square. Stuart May was, for years, chairman of the National Hop Board. The last hop pocket to leave Peasmarsh was in 1976 from Woodland’s Farm, so claims John Bull who loaded them on the lorry. The loading of the pockets, which were all of six feet long, was quite an art which I could never understand. As the pod of the lorry became full, then a layer was put across just overlapping the sides, and as a long rope was pulled down the middle is where I became puzzled. This was repeated for some four or so layers and some were slung over the cab held by the same long rope, which when pulled tight held the whole load firm and safe. If any of Jempson transport old drivers are about they would be able to explain this loading technique. When one thinks back one sees the death of a great industry, with a memory fading rather quickly. A man, with surprise in his face, said to me not long ago “did Peasmarsh once grow hops?” If he had only looked at the names of places and property he would have known.

With luck, I am hoping to deal with other remains of other once productive elements of the village and meanwhile express thanks for Jempsons supermarket for keeping up the economy although its only distribution, and not production.

Top: Fred Lancaster dealing with rubbish from new Hop Picking Machine 1954. Centre: Joan Beaney (Bailiffs Daughter) off for another load Bottom: First operators new Hop Picking Machine, Sharvels 1954.

George Fisher; Alec Murrell (Dryer); Jimmy Paine