The Story of the Rye Harbour Lifeboat Disaster

The Alice of Riga

In the early hours of the morning of 15 November 1928 a chain of events started that was to lead to the worst Lifeboat disaster in the history of the United Kingdom.

The steamship Alice of Riga, a collier carrying a load of bricks, was making her way through ever roughening seas down the Channel. As she rounded Dungeness Point the weather worsened and huge seas began breaking over her bows. She was an old ship and struggled to keep from being blown off her westward course. Visibility was reducing by the minute and her stern lights may have been extinguished by the breaking waves as her crew struggled to fight her through the storm.

The Smyrna

Behind her but unseen in the mountainous seas, a larger vessel the Smyrna, a German merchantman, steamed in the same direction equally unaware of the other ships presence. Although the Smyrna had been forced to reduce speed and proceed very slowly she still gained on the unseen Alice and as the two vessels approached Fairlight at about 4am. a shuddering shock ran through both ships. The Smyrna had ploughed into the back of the Alice.

The Captain of the Smyrna put his engines into reverse. He could see nothing of the Alice. After a period of time which seemed like an eternity, signal lights flickered from the stricken vessel. She reported serious stern damage, complete rudder failure and water making fast in the engine room.

With no means of manoeuvre the Alice was at the mercy of the storm and it was evident she would soon be driven ashore. The crew would have to be rescued before she sank or was smashed to pieces on the rocks or shore. The captain of the Smyrna quickly assessed the situation. It was impossible to get lines across as the seas were too rough but he deployed many ladders, life buoys and ropes over his lee side. Volunteers were called for to man the lifeboats but it was decided not to attempt to lower them before daylight.

The Distress Signal

The 5.5. Smyrna sent a distress signal which was picked up by North Foreland Radio. They relayed the message to Ramsgate Coastguard who recorded at 4.47am. “Steamship Alice, Riga, leaking-danger-drifting SW to W 8 miles Dungeness 04.30”. This message reached Rye Harbour Coastguard Station at 4.55. Maroons were immediately fired, calling out the crew and launchers.

Meanwhile events had taken another turn off Fairlight. Just after five the Alice signalled to the Smyrna that the crew were abandoning the ship and taking to the lifeboats. The Smyrna was put in as close as she could get and after a while the lifeboats were seen through the gloom and crashing seas. For the next hour the crew of the Smyrna performed heroic deeds, plucking men from the sea with little regard for their own safety. In all 13 men and one woman (the cook) were saved. Not one life was lost.

The Delay

Now comes the terrible tragedy of the situation. At 6.12 am. the Ramsgate Coastguard received a second message from the Symara reporting that the entire crew of the Alice had been saved and the Rye Harbour Lifeboat would no longer be required. At this time the men of Rye Harbour were making their way to the boathouse situated a mile and a half along the beach towards Winchelsea. Despite the terrible weather there were no shortage of volunteers to man and launch the boat.

The tide was out and so the Mary Stanford, a non righting Lifeboat powered only by oars and sail, had to be dragged across the beach. There was a force ten wind blowing and several attempts had to be made before the vessel was successfully launched. It was 6.45am. By this time the crew of the Alice were all safety aboard the Smyrna.

Major Hacking of Cadborough Farm, Rye was one member of the crew not to make it in time for the launch. He had not heard the Maroon over the noise of the fearful storm. When he eventually got the message by phone he galloped his horse over the fields and arrived in time to see the Mary Stanford headed out to sea.

At 6.50 the message NOT TO LAUNCH was received at the Rye Harbour Coastguard Station and immediately relayed to the Lifeboat House, just five minutes too late. A recall white verey light was fired but in the terrible conditions it went unseen by the lifeboat crew. Shouting and waving oilskins the launchers ran along the beach in a vain attempt to catch the attention of the brave men in the small boat now bending their backs pulling on the oars and looking ahead for signs of the Alice.

What happened aboard the Mary Stanford after she disappeared from view on her rescue mission can only be a matter of conjecture. She would have made for the last known position of the foundering Alice.

Sighted at Nine

Mary Stanford was sighted at 9am. by the mate of the 5.5. Halton in a position 4 miles WSW of Dungeness and appeared perfectly alright at that time. They might have been continuing their search or they could have been waiting for the tide. The Rother at Rye Harbour is not navigable for about seven hours when the tide is out.

The next recorded sighting was at lO.3Oam. John Prebble, the Coastguard on duty at the Rye Harbour lookout saw the Mary Stanford SSE about two miles from the lookout. The gale was still blowing at force eight and there were intermittent heavy squalls. He watched for about three minutes when she seemed to change course and head for the harbour. As she altered course she was obscured from his view by a squall. At about the same time two other men were watching her from the top of a sand dune at Broomhill. She was heading towards the Harbour “she seemed to turn round to the shore, and as she turned she toppled over. She was then on the crest of a huge wave’.

Coastguard Alerted

The coastguard was alerted and men rushed to the beach to help. The Mary Stanford had capsized in the raging surf off the Harbour mouth. Alfred Homer, a member of the St. John Ambulance Brigade, told of the desperate attempts that were made to resuscitate each man as he was washed ashore. The bodies of Joseph Stonham, Robert Pope, Roberts Cutting and Maurice Downey were the first to be given up by the sea.

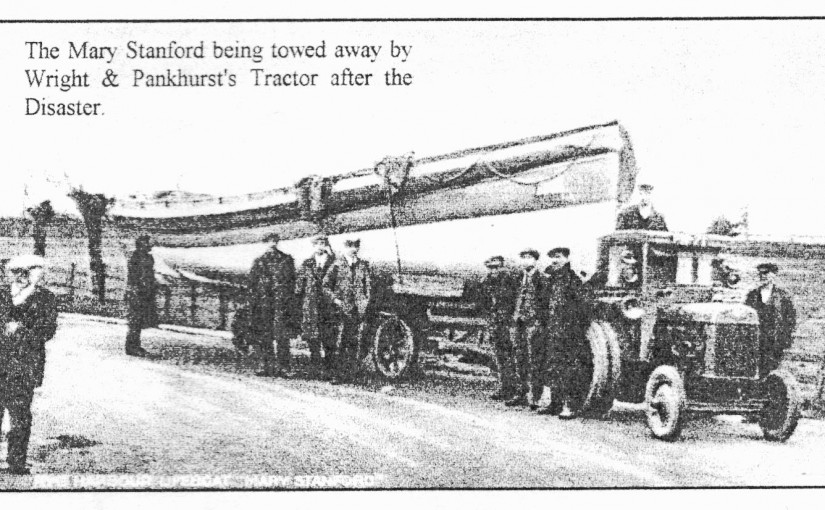

Then the Mary Stanford herself was deposited on the sands at Camber. A Tank had to be called from the 2nd. Tank Regiment’s base at The Suttons to lift her. Underneath were found the bodies of Charles Pope and Walter Igglesden.

A Terrible Day

Through that terrible day men searched the shoreline and the bodies of nine more of the valiant men were recovered. They were Herbert Head, the coxswain, James Head, Alexander Pope, Charles Southerden, Leslie Clark, Arthur Downey, Albert Cutting, William Clark and Herbert Smith.

The body of Harry Cutting was recovered from the sea three months after the disaster but the remaining member of the crew, John Head, was never found.

Every Family Affected

The small village of Rye Harbour was decimated. Stripped of its finest and most brave young men. Every family was affected. The list of the dead tells its own story of fathers and sons of brothers and relatives. The nation mourned and a funeral at the small village church was attended by great numbers including a representative of King George V. and members of the Latvian Government.

The memorial to these heroes in the Churchyard at Rye Harbour has immortalised their names and is an example of courage and devotion to duty that inspired the people of Rye Harbour to pick up their lives and go forward into the future.

A disaster fund was set up to help the bereaved families and realised over £35,000.

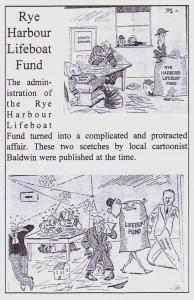

Rye Harbour Lifeboat Fund

The administration of the Rye Harbour Lifeboat Fund turned into a complicated and affair. These two sketches by local Baldwin were published at the time.

The Lifeboat Station at Rye Harbour was closed in 1929 but in 1966 an inshore lifeboat was introduced and has saved many lives in the 34 intervening years.

This carries on a tradition that started as early as 1803 when the first recorded mention of a Rye lifeboat was made.

‘Waves may batter men’s bodies, but they cannot touch brave souls. Search Sussex, search England and you could not find braver men, every man was a volunteer.’

“Rye’s Own” May 2000

All articles, photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2015 Cinque Ports Magazines Rye Ltd., Guinea Hall Lodge Sellindge TN25 6EG