By David Russell

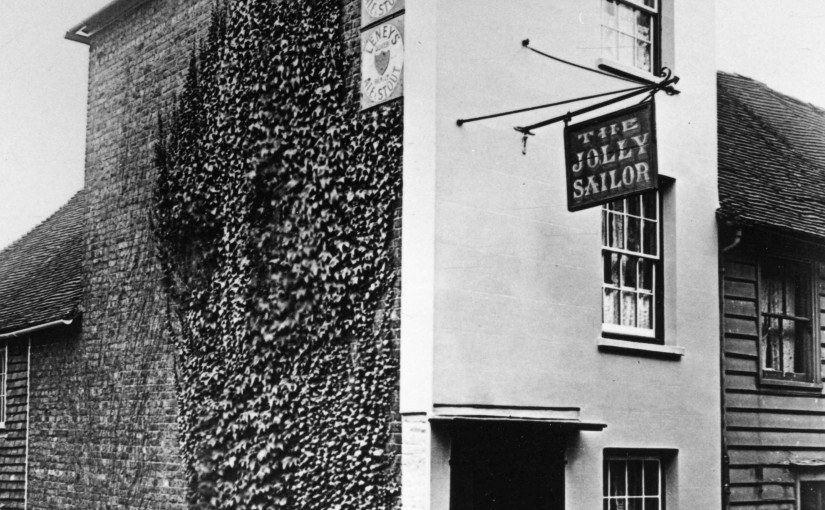

The Jolly Sailor first opened its doors as a beer house in Watchbell Street in 1830. Landlord Thomas Hearsfield applied for a full licence in 1831, and again successfully in 1832. Both applications were supported by a petition organised by local vicar John Myer who was mayor of Rye in 1828. He urged the magistrates to consider:

‘That your petitioner has legally settled in the said town, has a wife and three small children wholly dependent on him for support. That your petitioner has opened his house under the late act for the sale of beer, which has been regularly conducted by him without any complaint from his neighbours or any other persons whomsoever. Your petitioner begs leave to state that there is no licensed public house in Watchbell Street and the nearest one is the Red Lion. That your petitioner has been informed and believes it to be true that the public in general would be better accommodated if the house of your petitioner were licensed as a regular public house and that he has been advised to apply for the same and has in pursuance of such advice caused the regular notices to be given of his intentions of making such application. He therefore most humbly prays your worships will be pleased to take his case into your consideration and grant the necessary certificate that will enable him to apply to the excise for the necessary license and should your petitioner succeed he hereby most faithfully promises to keep as regular a house in all respects as he has before done. And your petitioner states John Hearsfield is a fit person to keep a public house.’

Notwithstanding the support of the vicar and 45 residents, within 10 years the Jolly Sailor had become a common lodging house for poor travellers and itinerants, as in 19th century Rye there was a big demand from the travelling poor for the basic accommodation the Jolly Sailor had to offer.

In 1839 John Hearsfield died leaving the Jolly Sailor and his estate to his wife Mary, who ran the pub until 1841. She also inherited two cottages located behind the pub in Hucksteps Row, and a house in Watchbell Street.

On census night 1841 the Jolly Sailor had 11 lodgers. As well as Mary Hearsfield and her two children, (perhaps the third child had died), the lodgers consisted of a shoemaker’s family of four, two cap makers, a weaver, a painter, an agricultural labourer and two ‘independent’ women, aged 25 and 26-years old.

In the same year Mary Hearsfield left this rumbustious and high spirited pub to run a nearby shop, which remained in the Hearsfield family for the next 30 years.

“The Jolly Sailor”, said local author Peter Ewart, “was no ordinary tavern, even in those days. Patronised by the roughest elements of the public its interior was the scene of many sinister doings during its comparatively short history.”

In 1841 James Dawson took over from Mary Hearsfield to become the pub’s longest serving landlord, until 1874. Dawson became a well known local character and during the 1850s and ’60s was often to be seen standing in the pub doorway beckoning a welcome to many a passing stranger.

Dawson was also landlord during the Rye ‘treating scandal’ during the general election of 1852, when surprisingly, given the size of the house, he hosted not one, but three free dinners with free alcohol funded by the parliamentary candidate to the tune of £15. 5s 6d. In today’s terms this was about £880!

The next landlord was William Watts who, like his predecessor John Hearsfield, also owned property in Hucksteps Row. A guide book points out that ‘for many years these small dwellings were considered so far gone they were thought unsuitable for occupation’. But William Watts ‘took an interest in them and several were in consequence restored and tenanted’.

Unfortunately for him, some of his tenants were not always on their best behaviour or the most prompt with their rent. In 1879 a group of them attempted to have him indicted for serving porter out of hours on a Sunday morning, apparently because he was demanding they pay their rent arrears.

William Watts won the case and a tenant was evicted. The case report informs us that the Jolly Sailor, even when it was ‘closed’ as a public house, traded fish, eels, pork and vegetables, direct from its back gate to the inhabitants of Hucksteps Row and beyond. Watts also sold porter and beer from the back door, which was carried away by the locals in earthenware jugs and bottles.

Complaints about Jolly Sailor customers were regular and continuous, and the police described them at various times as ‘gypsies, hop pickers, rag and bone collectors and those who go mushrooming on the marsh’.

The Jolly Sailor also provided accommodation for the many street entertainers who visited the town in large numbers during the second half of the 19th century. This group of customers included the owners of dancing bears, one man bands and various street musicians. While their owners slept the bears were chained and locked in a shed at the rear.

On one occasion the landlord was accused of overcrowding, and to have accommodated 30 lodgers in one night. This turned out to be false, but it was the type of rumour which fed into local folk-lore about the Jolly Sailor over the years.

Another widely circulated story was that the pub used a system of taught ropes slung across a room at chest height, for lodgers to drape themselves over in order to sleep. They were woken up in the morning by the landlady slackening the ropes!

In 1886 Thomas Marsh took over the Jolly Sailor as his first pub. He was told “the Jolly Sailor is a difficult house. Some very peculiar characters resort there at times, and great care is needed on the part of the landlord.”

Many an incoming landlord was advised by the magistrates of the difficulties he might encounter in the pub particularly if he was new to the town. In 1900 new landlord Henry Wilson was told: “This is not a first class house and it is a difficult thing for a landlord to keep his customers in order.” And in 1909 the final landlord, John Best, was advised: “This house requires a great deal of supervision. You must be careful in the manner in which it is conducted.” However, in 1910 the Jolly Sailor became yet another victim of the 1904 Licensing Act and was closed down.

Twenty years later Adams Guide to Rye and District informed its readers about ‘another abandoned inn – perhaps the most sinister to a bygone generation – the Jolly Sailor, which, could its walls speak, would unfold tales as sordid and crime stained as many associated with the doss houses of the Bowery. Many a person I remember being hailed from the brick floored, smoky taproom, or sparsely furnished and cheerless upper chambers, where the tramping fraternity certainly encountered some strange bed fellows.’

“In my mind’s eye”, said the writer, “I still see the typical landlord, James Dawson, seldom without his churchwarden [a clay pipe with a 24 inch long stem], standing at the threshold of his pub bidding welcome to all and sundry of his customers. The Spartan accommodation provided was regarded as much superior to the alternative of passing the night in the vagrant’s ward of the workhouse.”

The original building, now a private house, still stands and portrays feint signage from its pub days of over a century ago.

From ‘The Pubs of Rye 1750-1950’ by David Russell.

This book, illustrated with around 100 photographs, is a new paperback, 282 pages, price £13.99.

It can be purchased at the Rye Heritage Centre, Adams of Rye and at Waterstones in Hastings. It is also available from the publisher, Lynda Russell at [email protected], or phone 01424 200227.

Rye’s Own December 2012

All articles, photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2015 Cinque Ports Magazines Rye Ltd., Guinea Hall Lodge Sellindge TN25 6EG