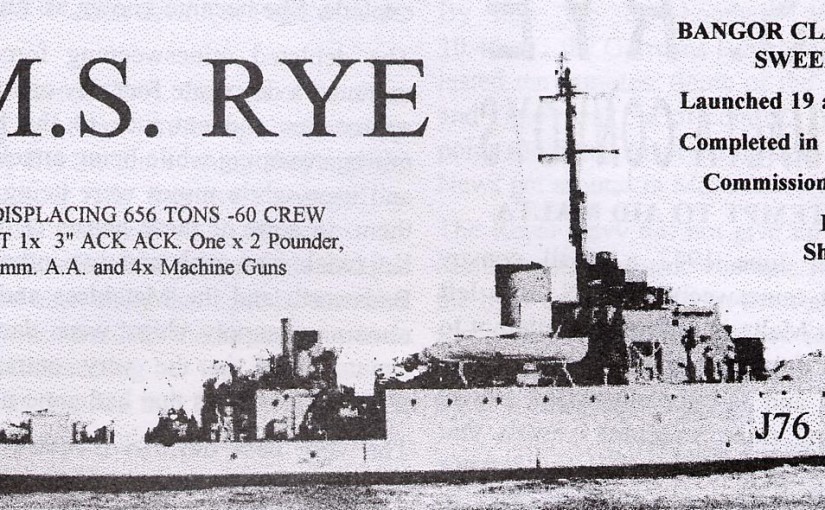

On a cold January morning in 1942 HMS Rye, a Bangor Class Minesweeper commanded by Lieutenant J. A. Pearson, slipped her moorings at a small Scottish port and put to sea on her maiden voyage. Sea trails off the east and west coasts of Scotland proved successful and because of the urgent need for sweepers at that desperate time in the War she was quickly pressed into service.

Minesweeper duties in the Dover Straights, just a stones throw from the Ancient Town from where she got her name, were swiftly followed by an attachment to an Atlantic Convoy down to Gibraltar.

Lieutenant Jim Pearson brought his new charge safely to The Rock and no doubt had time to ponder over the exploits and the fates of the three previous navel vessels that proudly carried the name “Rye”. The first, built in 1696 saw over 30 years service before being sunk on the breakwater at Harwich. The second, built in 1740 had a much shorter life, she was wrecked in 1744. The third Rye, built the following year, had a more successful career serving the navy well for 18 years before being sold for commercial use.

Pondering the situation and realising that his ship was in one of the most vulnerable theatres of the War at that time Jim Pearson might well have given the fourth “Rye” small odds on attaining even the four years life span of the second HMS Rye. Had he known where they were going next he would have reduced the odds further.

At Gibralta Rye joined up with Speedy and Hebe, both Halcyon Class sweepers and Hythe, a Bangor Class ship almost identical to Rye. They formed the 17th Minesweeping Flotilla under the command of Commander Jerome in Speedy.

Operation Harpoon

By early June 1942 it had become abundantly clear that the island of Malta, after months of sustained bombing and with its Harbours almost inaccessible because of the mine laying activities of the Germans and Italians, would have to be relieved. The population of the whole Island military and civilian alike, were under siege. Fuel was running dangerously low, limiting the activities of the remaining few aircraft that were heroically defending against continuous air attacks.

Malta had to be supplied or lost to the enemy making the task of winning the Middle Eastern phase of the War more impossible than it already seemed at that time. The crew of “Rye” were about to take part in a battle in which they played a large part. Malta held its breath.

Daring attempt to aid Malta

On the twelfth of June 1942 a small convoy, including the fleet minesweeper H.M.S Rye, left Gibraltar for Malta in a desperate attempt to deliver supplies of food and war materials to the beleaguered Island and to supplement the almost exhausted remaining mine sweeping vessels that were fast losing the fight to keep Valetta Harbour open.

The Germans and Italians were dropping and planting mines in the approaches and entrance of the harbours on a nightly basis and it soon became evident, because of the loss to enemy action of so many of the vessels capable of clearing these shipping lanes, that the harbour would be closed unless something came to be done very quickly.

H.M.S Rye, three other fleet sweepers, Speedy, Hebe and Hythe were to do the job but first they had to get to Malta. The convoy was made up of six merchant vessels, escorted by the cruiser Cairo, nine destroyers and the minesweepers. A covering force was provided made up of the battleship Malaya, two aircraft carriers, Argus and Eagle, three cruisers and eight destroyers.

The convoy was repeatedly attacked by both surface vessels of the Italian Navy and from the air by both German and Italian bombers. Four of the merchantmen were abandoned or sunk. The destroyer Bedoin was lost. Both the cruiser Liverpool and the Destroyer Partridge were badly damaged. During these actions Rye shot down two enemy aircraft. She also picked up survivors from the SS Tanimbar and SS Chant. Rye and Hebe were ordered to sink the SS Kentucky, a tanker whose engines were out of order due to a near miss from bombs. Rye took off the crew after which both Sweepers bombarded the Tanker with gunfire, setting her on fire.

Rye hits a Mine

In the approaches to Malta, Hythe cut a mine which surfaced ahead of H.M.S Rye. The Rye hit it directly on her bow and between the mine’s horns, shattering its internal mechanisms. The mine bumped right down the side of the hull but did not explode. Thereafter she became known as the “Lucky Rye”.

The depleted minesweeper force at Malta had mounted a desperate four day operation to keep the approaches and entrance to the harbour clear of mines, sweeping while being attacked by M.E. 109s and even while mines were being dropped around them. In spite of these heroic efforts the destroyer Kujawiak was sunk and two other destroyers Badsworth and Matchless and the supply ship Orari were damaged by mines, the merchant vessel in the very entrance to Valletta Harbour, by mines that had gone undetected.

The very next day, Rye, Speedy and Hythe, all surviving the passage to Malta damaged but still operational, went to work. Hebe was out of action for some time due to repair. From 17 June until the end of that month they destroyed no less than 60 mines and cleared the approach channel to a distance of three miles from the Harbour.

By mid August the minesweepers were on top of their task and submarines were again able to operate from Malta. Food and Fuel supplies were at an all time low however and a convoy with supplies was desperately needed.

Operation Pedestal

We have all heard of “Operation Pedestal”, made famous by the classic film “The Malta Story”. The saga of the oil tanker Ohio whose gallant entry into the Grand Harbour on 15 August signalled the turning point in the Island’s war and resulted in the unique George Cross award to Malta and her long suffering population. But what of H.M.S Rye’s contribution to Pedestal? They have not been so well publicised. Let us put the record straight.

On the 13 August 1942 Rye was detached from the other ships in her group and set off with the motor launches 121 and 168 to assist the destroyer Penn with the tanker Ohio.

At 16;43 Lt. J.A. Pearson RNR, Captain of the Rye, reported in his log that they were being shadowed by enemy aircraft. At five in the evening they sighted the Ohio. Half an hour later they were engaged by enemy aircraft and attacked with torpedoes. 15 minutes after the attack Rye had joined Ohio and the Penn. The Ohio had been badly damaged by then and the crew had been removed to the destroyer which was in the act of reconnecting her tow wire. Towing was resumed. It was decided that Rye’s sweep wires could be used for towing and by 6;15pm they were attached to Ohio and Penn.

Rye Disappears from Sight

Thirty minutes later Rye was attacked by about 16 aircraft and disappeared in plumes of water, she emerged unscathed, the bombs had missed her by 20 feet! At 8;30 that evening the tow was continuing towards Malta, then the dive-bombers came, putting Ohio out of control and forcing the Captain of the Penn to give the order for both Penn and Rye to slip the tow lines. Ohio, by this time listed badly to port, she had suffered more damage, her steering was impeded by blows to her stern.

H.M.S Rye went alongside Ohio at ten that evening and a boarding party under Leading Seaman Rowland Prior reconnected towlines that had been hastily repaired. With Rye towing ahead and Penn with a line attached from her bow to Ohio’s stern as a steering device, towing recommenced at a painfully slow four knots towards Valetta.

A few minutes after one the next morning (14th August) both towlines parted. The Penn and another destroyer the Bramham, went alongside the Ohio, one on each side and attached lines. Rye made a 10” manila fast and towed from ahead. At dawn the tows were slipped and repaired.

Rye went alongside Ohio at 7.15 and passed the tow rope. By a quarter to eight the tow was under way again and other ships were rushing to their assistance. Speedy, Hebe and Hythe with motor launches alongside set up a protective screen around the ships and in a further desperate attempt to get the floundering oiler into port the Penn secured alongside the Ohio to help with steering after the Tanker had veered 80 degrees to starboard and parted the towlines for the forth time. At nine the destroyer Ledbury appeared on the scene and assisted with the towing.

By now the dive-bombers were back and at 10.40am, the Germans launched a fierce attack that lasted ten minutes. Some of the lines were severed and Ohio went out of control. This was the lowest point and many involved thought she would be lost. News got around in Malta that she had been sunk.

The Royal Navy did not give up and at sea off the Malta coastline heroic attempts were made to repair the lines and get Ohio on her way again. A tug was sent from Valetta. Rye helped re-rig the tow wires and Bramham got alongside the stricken vessel and the tow continued.

Rye led them in

At 12.45 in the afternoon Rye was ordered to slip her line. The tow proceeded with the Malta tug towing from ahead, the Penn and Bramham alongside the Ohio and Rye sweeping for mines ahead.

The scene as the Tanker was delivered by the Royal Navy into the Grand Harbour does not have to be imagined. The event has been reconstructed very accurately in the motion picture “The Malta Story” the Ohio, lashed to Penn and Bramham with bomb holes pouring smoke enters the Harbour to the relief of the Islands entire population. The siege was lifted. H.M.S Rye’s brave story is a part of this saga of the sea. The original insignia of the ship was presented to the town after the vessel was de-commissioned and is housed at Rye Town Hall.

Lucky Rye

H.M.S Rye continued her work in the Mediterranean with the 17th Minesweeper Flotilla. She was involved in many adventures and skirmishes but her luck held and by the time the Allies were gaining the whip hand in Africa the crew had become seasoned veterans. Even though the tide of war was changing the decks of a small minesweeper were still a very dangerous place to be. Rye was at the Sicily landings, sweeping ahead of the invasion forces and later she performed the same dangerous job for the invasion of Italy.

Rye left Malta for the last time in early October 1943 with a small convoy to Gibraltar. Whilst acting as an escort on the north side of the convoy and laying a smoke screen, she ran out of smoke canisters and was ordered to swap places with her “chummy ship” H.M.S Hythe, which was on the south side of the convoy. That night Hythe was torpedoed and sunk. The Rye picked up twelve survivors, two of whom subsequently died. The Hythe was sunk by U-Boat 371 off Bougie, Algeria on 11th October 1943. The event saddened the hardened seamen on Rye. The Hythe had been with them almost from the start and the two ships had worked together and their crews had spent off duty time together now the partnership was over and Rye sailed on without her sister ship.

Rye’s luck nearly ran out on Christmas Eve 1943 on passage for the UK on home leave. In the Straights of Gibraltar she was rammed by one of three Liberty Ships coming in. Rye’s bow was severely damaged. She altered course for the Azores and arrived there safely after a difficult voyage. The bow was filled with concrete and in this precarious state she ran the gauntlet of storms in the Bay of Biscay and steamed back to the UK and her home port of Troon, where a new bow was fitted.

The Normandy Landings

H.M.S Rye was back in action in time for the Normandy landings in June 1944. With a new commander Lt. F Williams and as part of the 14th Minesweeper Flotilla the “Lucky Ship” went to war again. First sweeping the cross channel seaways for the invasion forces, then the “Omaha” beachhead ahead of the American landing craft. On one sortie she came under heavy fire from shore batteries and had to beat a hasty retreat, cutting her sweeps.

Rye then took part in sweeping the approaches to the Beachheads which were constantly being re-mined by the enemy. This sweeping was interspersed with escort duty between the UK and “Omaha”

The Flotilla worked its way down to Brest, where Rye was anchored for six weeks and virtually became “Brest Radio Station” for that area of the Allied armies. The telegraphists worked a tiring “four hours on, four off” shift, watch and watch about for six weeks.

Two U-Boats Surrender to Rye

After taking part in clearing the coastal waters towards Belguim and Holland she spent four weeks undergoing refit at Flushing. In May 1945 Rye was in Stavanger clearing anti-submarine mines, when two U-Boats came into the Harbour and surrendered to her. She subsequently came home to Edinburgh, then down to Swansea to sweep the Bristol Channel area.

Paid Off at Swansea

H.M.S Rye was paid off in Swansea in 1946. Sold for scrap on 24th August 1948 and subsequently broken up at Purfleet in September of that year.

After H.M.S Rye was broken up in 1948 a ceremony attended by some of the ships company was held in St. Marys Church, Rye when the ship’s White Ensign was taken into safe keeping. The Ensign is now located in the South Transept of St Mary’s.

The original insignia of the ship was placed in the care of the Town of Rye after the vessel was paid off and is housed at Rye Town Hall for safe keeping until such times as a new H.M.S Rye may be required by the Royal Navy

Legacy of Freedom

There were many brave Royal Navel ships that fought in World War Two. Each has it’s own story of heroism and achievement.

This was the story of ‘our’ ship and her brave crew. Time has passed and many of those men are no longer with us. Their exploits will not be forgotten and the legacy of freedom that they helped win back from the “abyss of a new dark age of tyranny” that Churchill promised if Hitler won the Second World War, still shines brightly today.

Reprinted with minor variations from the Millennium edition of “Rye’s Own”

Rye’s Own May 2004

All articles, photographs and drawings on this web site are World Copyright Protected. No reproduction for publication without prior arrangement. © World Copyright 2015 Cinque Ports Magazines Rye Ltd., Guinea Hall Lodge Sellindge TN25 6EG